Monday 2nd December to Tuesday 3rd December 2019

Having planned to meet friends in Bath to enjoy the famous Christmas market there we decided to break the journey and found a place to stay near the ancient site of Old Sarum.

From here we walked into Salisbury and visited the Cathedral. The original building was constructed between 1075 and 1092 but just five days after the consecration ceremony it was damaged in a storm and needed repairs: we felt that some people might have taken this as a sign of divine displeasure.

In about 1120 to 1130 the cathedral was rebuilt on a much grander scale, although some of these buildings have since been demolished.

Today there is a peaceful cloister which is said to be the largest of any cathedral in Britain.

In the Chapter House off the cloisters you can see the best preserved one of just four remaining original copies of the Magna Carta, dating from June 1215. This document covers such varied topics as the standardisation of weights and measures and the rights of the Church as well as the importance of legal due process and, crucially, the principle that no one, not even the king, is above the law. [Only time will tell if Boris, or Prince Andrew, appreciate this. . .]

The cathedral itself is lofty . . .

. . . and includes an extraordinary infinity pool font designed by William Pye for the Cathedral’s 750th anniversary. This is impressive, like an architectural indoor water feature and reflects a perfect image of the fan vaulting above, but unfortunately our photos did not do it justice.

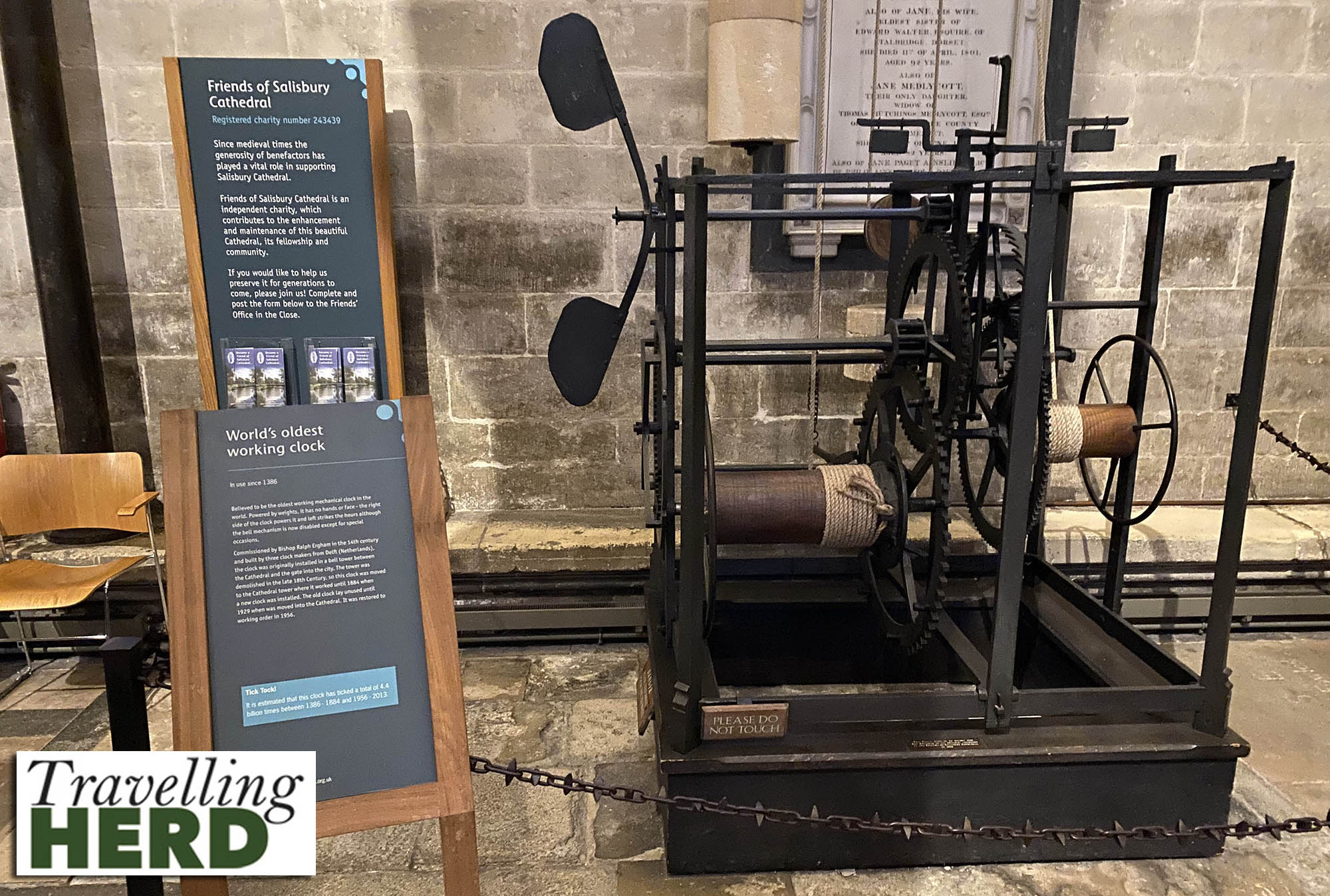

Salisbury Cathedral is also home to the world’s oldest working mechanical clock which dates from 1386.

The building was illuminated as we left and leaving the highest spire in Britain, standing tall and impressive behind us, we went in search of supper.

The following morning we went to visit Old Sarum, the site of the earliest settlement in Salisbury. An Iron Age hill fort was built here in around 400BC and the site was subsequently defended against the Vikings and used by the Romans, the Saxons and the Normans who constructed a motte and bailey castle and a large cathedral. William the Conqueror established it as one of his royal castles.

The footprint of this earlier cathedral can still be seen today.

Richard Poore, Bishop of Salisbury from 1215 to 1237, clashed with the Lord of Sarum Castle over a range of issues, including the quality of the drinking water, the conditions his monks had to endure and the morality of the Lord’s soldiers. Richard Poore was eventually driven out of the town, but before he left he secured permission from the Pope to construct a new cathedral outside the existing city.

Richard Poole presumably had the last laugh as the construction of the new cathedral brought work and prosperity. The new town, originally built to house the builders and craftsmen, soon became a thriving commercial centre with twice weekly markets, which are still held to this day. As Salisbury was now more successful than Sarum itself the old city declined and much of the stone from the royal castle was removed and reused leaving the ruins visible today.

The “new” city can be seen standing triumphant across the plain.

You can walk along the outline of the old cathedral.

From Old Sarum we drove to Tyntesfield, a beautiful Victorian gothic revival house to meet our long-standing friends, Liz and Martin. [Robert wants to call them old friends, because they are both older than him].

From the moment we walked up towards the house, we knew that every effort had been made to decorate the house for Christmas.

It is certainly impressive.

Each room was complete with a Christmas tree and a character from the house’s past, dressed in period costume, waiting to regale visitors with an historical anecdote or two.

It included a family chapel which we were told had never been consecrated because of its links to the Oxford movement.

Despite its beauty, Tyntesfield was literally “built on shit” as . . .

. . . William Gibbs, who extended the existing building in the 1860s, made his fortune from South American guano sold and used as fertiliser.

Video of the day:

Selfie of the day:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.