Wednesday, 20th November 2019

There were conflicting reports about whether it was possible to visit the Royal Palace, but we set off to try and gain entry, armed with our passports which we had been told we would need if we were successful. This quest proved to be an exercise in perseverance.

Initially we took the tram to the Nations Unies tram stop and walked a short distance to one entrance to the Palace. Here we were told by one pair of guards that it was always closed to the public and we were not allowed to take photos.

A little further down the street a second set of guards told us that we had to walk clockwise around the perimeter to a different entrance. On the way, we passed the Rabat Ville Railway Station which has a well tended fountain in front.

We also took some time out from our quest and visited the Art Deco Cathédrale Saint-Pierre situated on a pleasant circus, Place du Golan. Construction began in 1919 and it was inaugurated in 1921.

The two distinctive towers were added to the striking exterior in the 1930s and the interior is beautiful yet rather minimalist by comparison to many Catholic cathedrals we have visited.

From here we walked up the Avenue Yacoub El Mansour to another entrance to the Royal Palace where, on trying to walk through the gate, we were directed back down the hill towards a narrow and unassuming gateway we had passed on the way up.

Here we were asked for our passports and gestured through to the reception where we presented our ID and were asked to wait in a small room with another couple with Brazilian passports who were also on the same quest. After a short while our passports were returned and we were free to wander the compound at will.

The effort to gain admittance was in stark contrast to the lack of direction once inside the royal compound, which, like the Vatican, seems to be a city within a city. We strolled towards the minaret and the mosque.

And from here on towards one entrance of the Royal Palace itself.

A very pleasant policeman told us that we could go as far as the edge of the pavement to take photos but that we must stay on the pavement, behind the metal canonballs.

By this time it was nearly two hours since we had left the hotel and we felt this warranted a selfie.

The minarets in Rabat are visible beyond the royal mosque.

Walking back, the same charming policemen told us we had the option of leaving through one of three exits. He also told us that it was a short walk to the Chellah Necropolis and very kindly escorted us across the road, although traffic was relatively scarce here.

Morocco has traffic lights for both vehicles and pedestrians but it is still sometimes unclear when it is safe to walk across the road. Many drivers are very courteous and stop to allow you to cross. This confusion seems to be acknowledge by the fact that there are policemen stationed at many junctions and pedestrian crossings around the city blowing their whistles directing both vehicles and pedestrians. Sometimes we felt we were a welcome distraction for these law enforcers watching the traffic flow.

We left the royal compound via the exit where previously we had been sent back down the hill to show our passports and walked on to Chellah, an ancient site where Roman ruins lie within a walled medieval Muslim burial ground.

The approach is impressive with the restored pink walls rising above well-tended, lush, green lawns.

A sign at the entrance informed us that the Necropolis was currently closed but we could visit the rest of the site.

Once a properous Roman city, called Sala Colonia, stood here. The Artisanal District [below] was excavated between 1962 and 1968 and was identified because of three oil presses with pressing floors and settling vats. A bakery has also been uncovered but we found it difficult to identify these different trademen’s areas precisely.

Sala Colonia was mentioned by Pliny and other Roman authors and was strategically situated above the mouth of the river. A helpful sign at the entrance informed us that the town was repeatedly attacked by Autolole tribesmen on elephants and the a high defensive wall and ditch were built in response.

The remains of a triumphal arch and a forum are still visible but the ancient site was abandoned and in the tenth century Chellah became a military Merinid fort with a minarets and a madrasa. Here, as at Palais el-Badi, white storks nest on the walls on the south of the site, which is more sheltered. White storks live as colonies and there are said to be around 100 nests in and around Chellah.

There is also an eel basin, which was originally part of the washing rooms for the Merinid mosque and was fed by an underground aqueduct. The eels who live there are said to watch over the saints of Chellah as well as the mausoleums of the Merinid kings buried here. There is also a tradition that if a women feeds eggs to the sacred eels she will become pregnant.

We did not see the eels, but there was an elderly woman keeping watch over the site surrounded by chickens and cats of all ages, including this friendly kitten. We assume the woman also had a trade selling eggs to feed to the eels. Walking back down towards the main city this praying mantis turned to look at us when we stopped.

The Mausoleum of Mohammad V had been closed when we visited the day before but we had read that you could go inside so we returned to the Hassan Tower compound and found that the Mausoleum was indeed open. Visitors climb up steps to enter and are then on a mezzanine floor Inside the monument looking down. The sarcophagus of Mohammad V lies under the central twelve-sided dome whilst those of his two sons, King Hassan II and Prince Adballah are placed in two of the corners. The interior is intricately decorated and the mahogany ceiling is richly carved with muqarnas [stalactites].

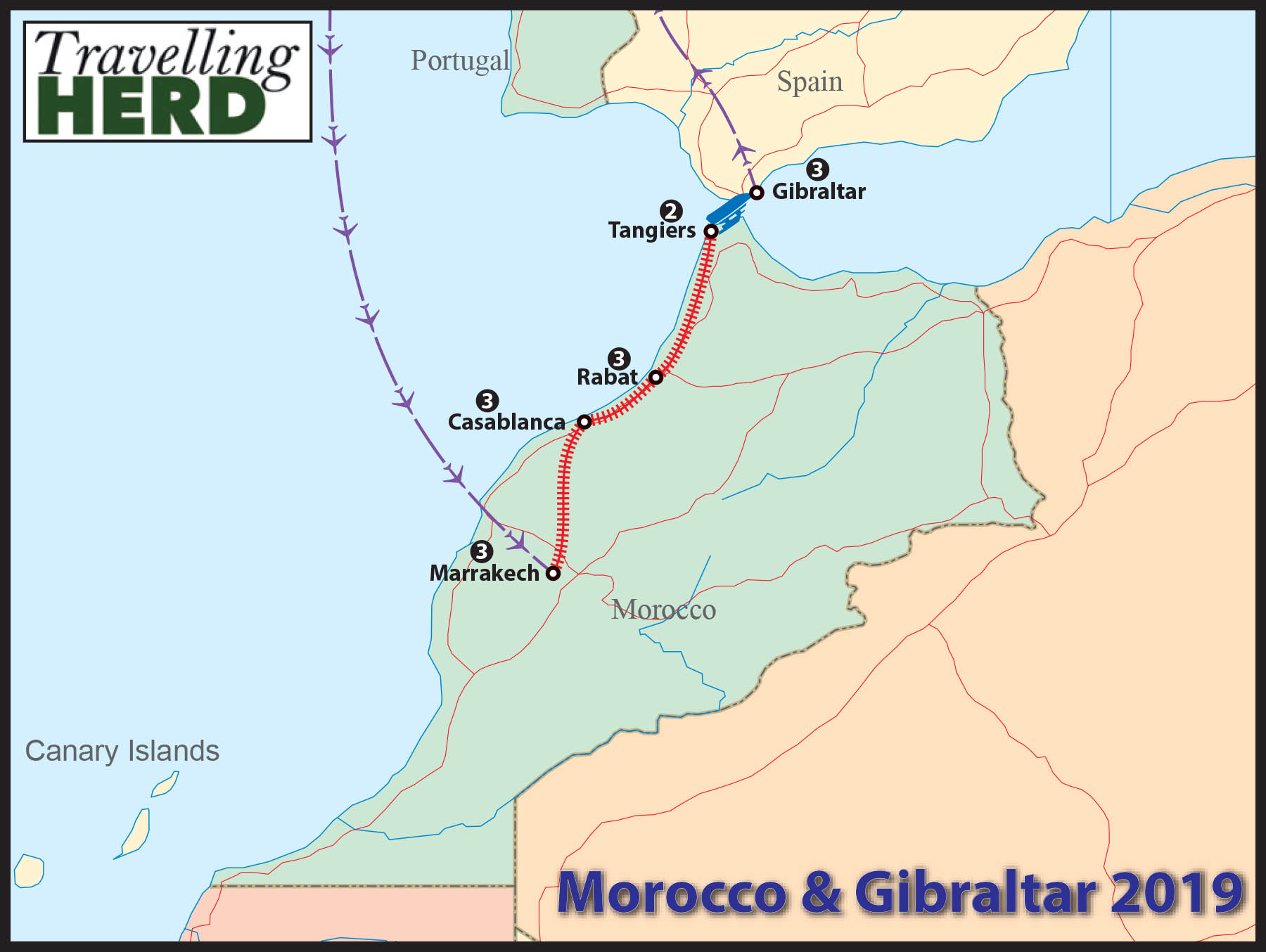

Route Map:

Selfie of the day:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![Rock[s and] the Kasbah, Rabat](https://i0.wp.com/iciel.uk/imagesTH/19-09-Morocco/Post8/19-09-08-feature.jpeg?resize=510%2C510)