Thursday, 14th November 2019

Following a leisurely breakfast, we set off to walk round Marrakech. Our walk led us along tree-lined boulevards with wide pavements to the Koutoubia Mosque.

The city was founded in 1062 by Youssef ben Tachfin, the leader of a tribe of nomadic warrior monks known as the Almoravids and it became Morocco’s second capital. In 1147 the Almohads took over control of Morocco’s major cities and it was under this dynasty that the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakech was built.

The minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque rises proudly above Marrakech and dominates the skyline. Its continued supremacy is due to a century old piece of legislation introduced under French colonial rule which remains on the statute books to this day: it is decreed that no building in the Medina (old city) should be taller than a palm tree and no building in the New City should rise above the height of the Koutoubia minaret. We were unsure whether all palm tress are aware of this restriction or whether one might, inadvertently, in a season of plentiful water and in a burst of ecological enthusiasm exceed the accepted height.

The minaret itself is 77 meters tall and complies with the architectural conventions of Almohad architecture in that its height is equal to five times its width. Each of the four sides features a different decorative motif.

The current mosque was built on the site of an earlier eleventh century one which was said to be incorrectly aligned with Mecca. The remains of this building have now been excavated and can be seen on the northern side of the Koutoubia Mosque.

From here we walked to the city’s main square – the Jemaa el-Fna – which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001.

In the mornings merchants sell fruit, freshly squeezed fruit juices, nuts and sweets and there are snake charmers and henna tattoo artists plying their trade.

Men with monkeys on chains offer them as props for tourists’ photographs but we gave these a wide berth as we would have preferred to liberate these animals from a life providing entertainment for profit.

In the evening, the square becomes host to stalls selling street food whilst dancers, musicians and storytellers perform where, once, criminals were executed then their heads pickled and suspended from the city gates. Thankfully nothing of this more macabre past remains. From the square, the souks radiate out into the maze of streets in the northern half of the medina, a living testament to the city’s merchant trading history.

Unfortunately the Ben Youssef Medersa has been closed for renovations since 2018 and is not expected to open until 2020 so we were unable to visit, but from the Jemaa el-Fna it was a short walk to the Saadian tombs which were rediscovered in 1917.

We wondered how such an imposing mausoleum could have been “lost”, but the guidebooks provided the explanation.

There is an oft-repeated cycle in Morocco’s history in which idealistic nomadic tribes overthrow the decadent rulers, now established in the cities, only to become, over time, decadent and debauched city-dwellers themselves. Thus the Almovarids were ousted by the Almohads; the Almohads were overthrown by the Merinids who were in turn deposed by the Idrisid interlude [a single ruler]; the following Wattasid dynasty was succeeded by the Saadi dynasty which was succeeded by the Dila’i interlude [another single ruler] and then the Alaouite dynasty took control [1666 to 1957]. Although the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Ismail tried to eradicate all traces of his predecessors, out of a deeply ingrained respect for the dead, instead of destroying the site of the Saadian tombs he raised a wall around the entrance to the necropolis, which was then left untended for two centuries.

Today you enter through a narrow passageway and find yourself in a tranquil walled garden where we saw a couple of tortoises slowly grazing round the graves in the garden which has been planted with flowers symbolising Allah’s paradise.

The Almohad and the Merinid dynasties used this site before the Saadis, but the complex you see today was built by the Saadian Sultan Ahmad Al Mansour to be his own final resting place and comprises the Mihrab Room, the Room of Twelve Columns and the Room of the Three Niches all of which are sumptuously carved and decorated.

There is a short, respectful and decorous queue to be able to stand in the entrance to see the Room of Twelve Columns [see picture above] which is a white carved extravaganza, reminiscent of the Taj Mahal, but in this instance it is a monument to self aggrandisement rather than a labour of love.

The complex is indeed an area of peace and calm and it was noticeable that visitors leaving the site seemed quiet and contemplative as they passed us on their way out.

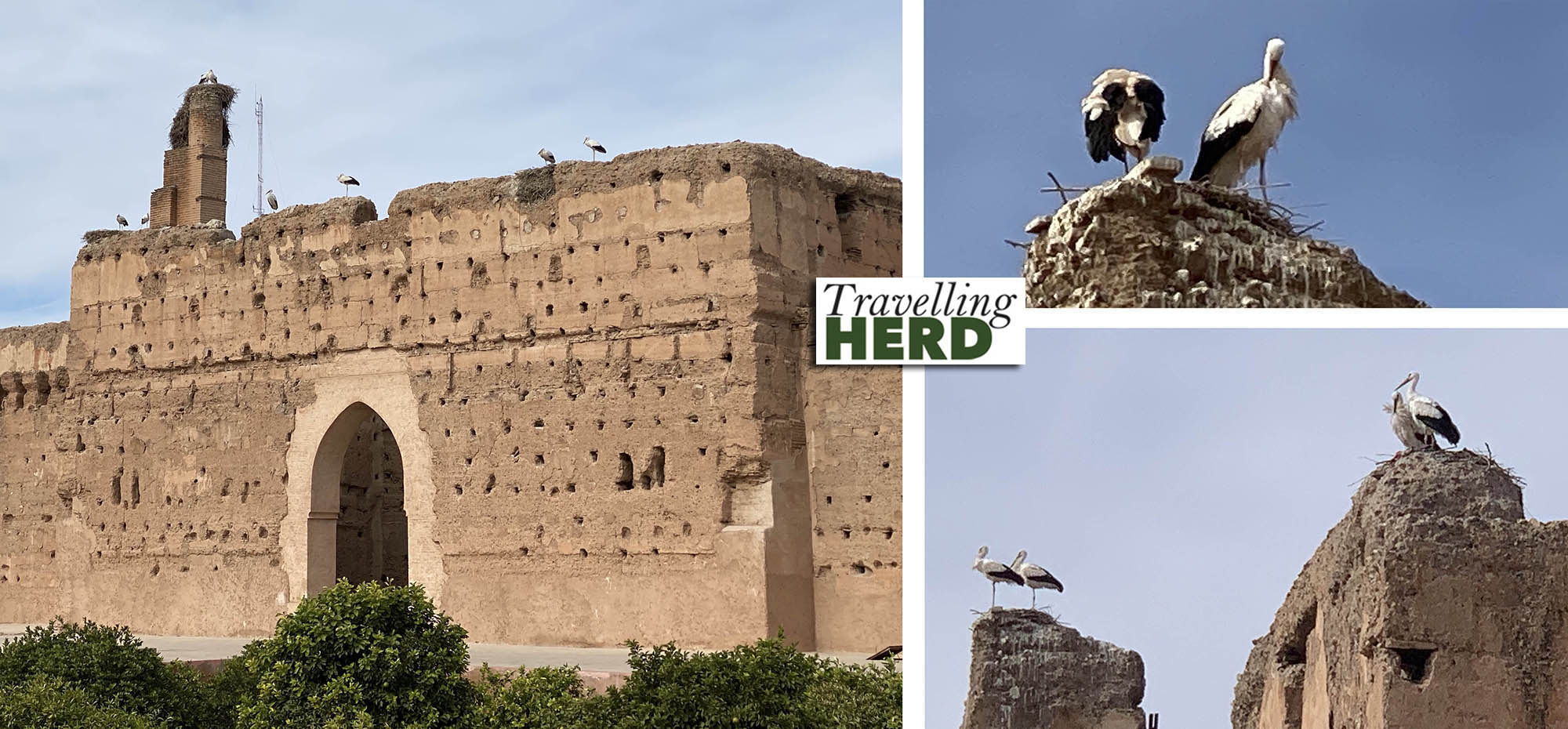

Close by is the Palais el-Badi.

The Palais el-Badi was built by Ahmed el-Mansour following his defeat of the Portuguese in 1578 at the Battle of the Three Kings. The palace was originally lavish and luxurious, decorated with Italian marble, Irish granite, Indian onyx and gold and was used to entertain visiting delegations from other nations. It was plundered for its riches by Moulay Ismail in 1683 who used the materials to decorate his own imperial city of Meknes.

The empty shells of the stable buildings and the pavilions remain, situated round a huge courtyard with pools and sunken gardens planted with citrus trees.

The cedarwood minbar [pulpit] from the original Koutoubia Mosque is displayed in one of the rooms but no photography was allowed.

Storks nest on the ruined ramparts and swoop gracefully away in search of food for the fledglings. As Matilda was positioning herself under an arch to take a photograph, a pigeon made a lucky deposit on her shoulder. She was thankful, given the size differential, that it was a pigeon and not a stork which had blessed her.

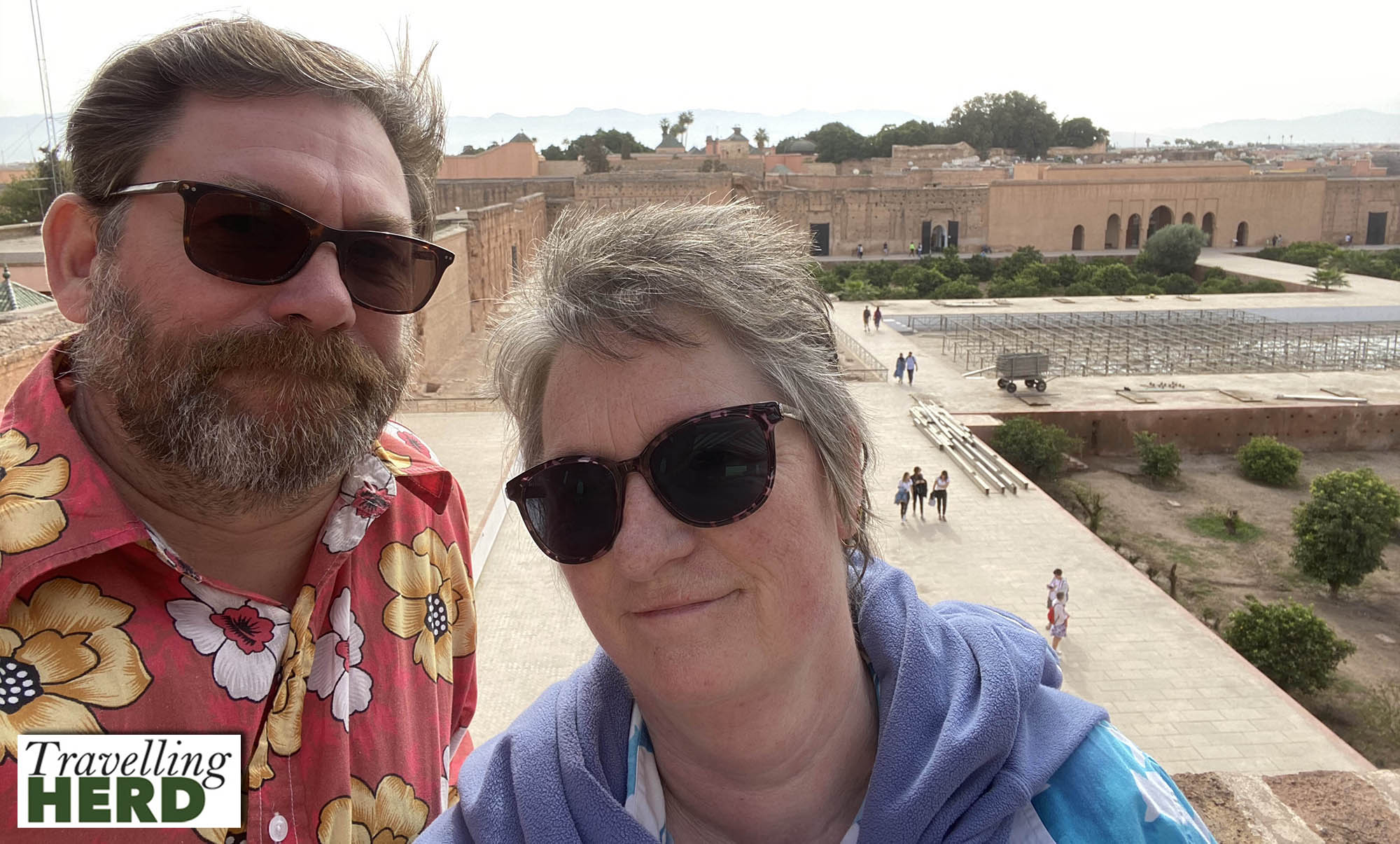

You can climb one of the towers to a terrace which gives fine views across the palace towards the Atlas Mountains.

From this vantage point it is easy to imagine how impressive this complex would have been when it was built and . . .

. . . the impact it would have had on visiting ambassadors.

Another short stroll took us to the Palais Bahia, which translates as “The Palace of the Favourite”.

This palace was built by in two phases, by a father and son, both in their time powerful grand viziers.

The first phase was built by Si Moussa and has apartments around a marble paved courtyard.

The second phase, built by his son Ba Ahmed between 1894 and 1900, is a series of apartments . . .

. . . with exquisite tile work and carvings, . . .

. . . striking stained glass features and planted gardens and courtyards.

The entire complex is beautiful and in its heyday with flowing water in the pools would have been sublime. In 1912 some renovations were made to accommodate the first French Resident-General of the Protectorate who took made this his home.

After a day’s sight-seeing, with the Menara Mall immediately opposite our hotel, we went over the road to one of the outside restaurants to eat, both opting for a variety of tagine – the local speciality served in a pot with a distinctive chimney-shaped lid which was removed with a flourish by the waiter.

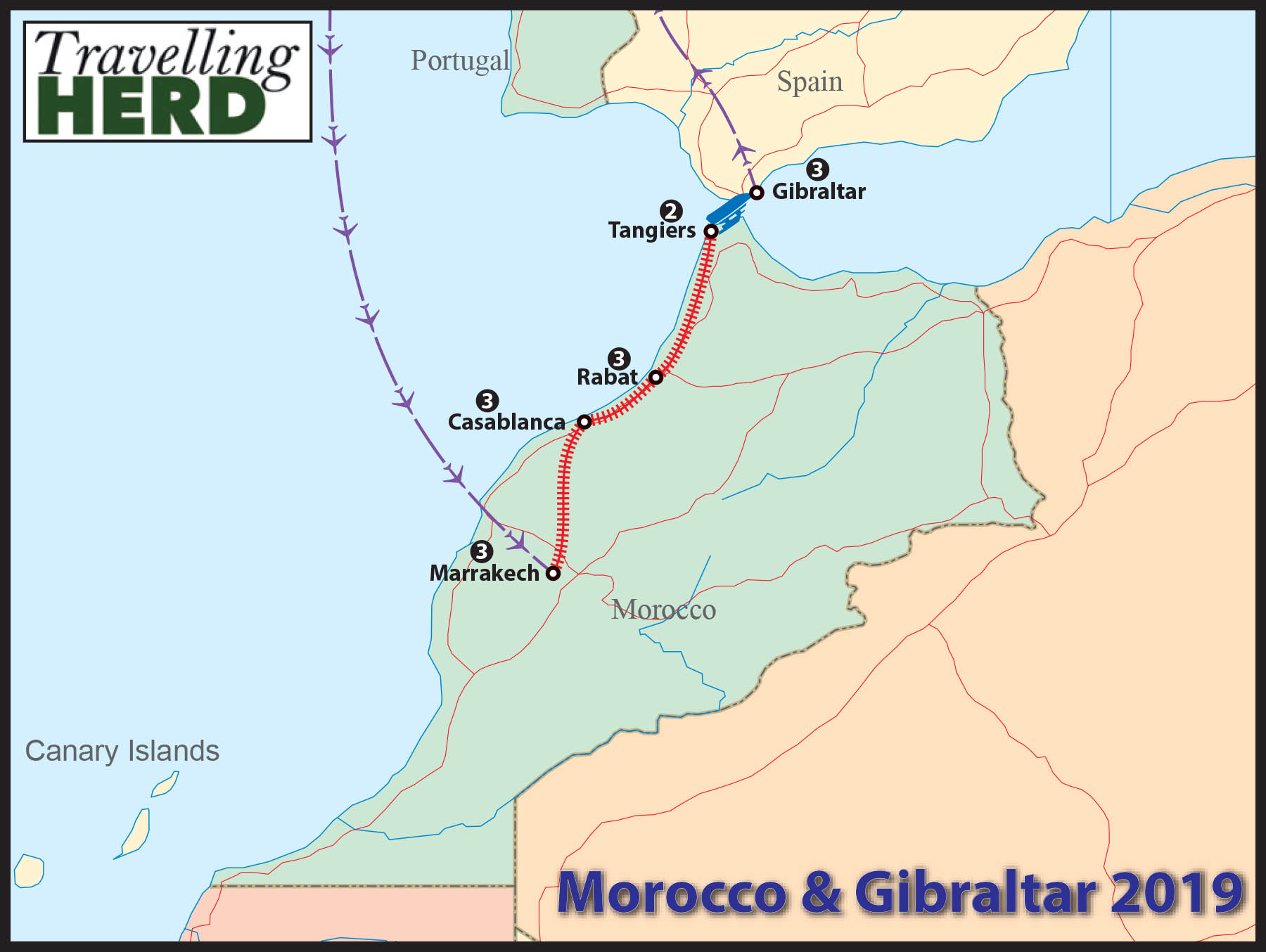

Route Map:

Video of the day:

Selfie of the day:

Dish of the day:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.