Read this blog: The one where Robert admired Urinals

Monday 21st and Tuesday 22nd August 2023

Having said a fond farewell to the fruity folly which is The Pineapple, we dropped our daughters at Larbert Station to travel home by train while we set off for Liverpool.

Both Robert and Matilda have visited before. As a student Robert came to play a rugby match against a local college and as a child, Matilda came on a family visit back to her father’s roots [he had cousins living in the city and was a life-long Everton supporter.] The only thing Matilda really remembers is the Roman Catholic cathedral which seemed so modern. The building which seems to have made the most impact on Robert, however, was The Philharmonic Dining Rooms and, in particular, the richly tiled urinals there. Some readers may not be at all surprised.

Having checked in to our hotel, we decided to walk around the city to get our bearings and as the hotel was close to the docks, we walked down to Pier Head to see the waterfront, past the imposing buildings known collectively as the Three Graces [see feature photo]. They comprise from left to right, The Royal Liver Building; the Cunard Building and the Port of Liverpool Building, all built in the early 1900s.

Between the Liver Building and the Cunard Building at Pier Head stands a larger than life statue of The Beatles. It seems a never-ending queue of tourists/fans wait to take their turn to have a photo taken with the bronze Fab Four. Robert managed a sneaky shot during the changeover without having to join the line.

Our route took us along the waterfront at the Royal Albert Dock then back inland towards the Anglican Cathedral. We passed the oldest surviving building in central Liverpool – Bluecoat Chambers in School Lane. It was built in 1716–17 as a charity school, but then moved to another site in 1906 and its original home is now an arts centre, known simply as The Bluecoat.

We walked along Rodney Street, Liverpool’s equivalent of London’s Harley Street with consulting rooms for all types of healthcare professionals, to the Anglican Cathedral in Liverpool, or the Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool. This is the largest cathedral and religious building in Britain, and the eighth largest church in the world.

Designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, it was constructed between 1904 and 1978. It is 207 yards or 189 m long, including the Lady Chapel [the first part of the building to be completed] making it also the longest cathedral in the world. The interior is indeed vast.

The design underwent a number of revisions and construction work was limited during WWI and WWII when Liverpool suffered more destruction and civilian deaths than any city other than London. The cathedral itself was damaged by bombs.

Unsurprisingly when Robert looked at GPSmyCity to plan a walking route, the majority of the tours were focused on The Beatles. Also, unsurprisingly, he chose to base our route on the one entitled Beatles Pub Crawl. Not far from the Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool is The Philharmonic Dining Rooms, commonly referred to as The Phil and the building which Robert most remembered from his previous visit. An ornate building with “exuberant interiors” in the style of a gentleman’s club, it is diagonally opposite the Royal Philharmonic Hall and has beautiful Art Nouveau metal gates but was unfortunately surrounded by scaffolding when we visited. Of course, Robert needed to go inside to reacquaint himself with the urinals.

Our next stop was not part of the Beatles Pub Crawl but a little bit of Germany brought to Liverpool.

Back on the Beatles’ trail, we visited The White Star in Mathew Street. This traditional pub is named after the shipping company. The White Star Line owned off the Titanic, which was therefore registered in Liverpool and so, although she never visited, she had the city’s name across her stern.

It is also known as the place where The Beatles played their first gig and where artists who played at The Cavern Club would come to be paid. The room at the back has a long bench seat with the names of The Beatles on plaques above.

The Grapes further along Mathew Street was another hostelry frequented by those who played at The Cavern Club. Artists often chose to go elsewhere for refreshment as The Cavern Club was an alcohol-free venue.

The Cavern Club is renowned as the music venue where The Beatles played regularly and Beat Music thrived in the 1960s. However, although it claims these historic links, British Rail closed the original building at 8 Mathew Street in 1973 to build a ventilation shaft for the city’s new underground railway loop. According to its own website, “The ancient warehouses above the Cavern Club were demolished while the cellar itself was filled with rubble and left like a sealed tomb for the remainder of the decade.” The Cavern Club reopened across the road at 7 Mathew Street in 1973 but the ventilation shaft was never built.

A statue of Cilla Black stands outside the entrance to the original venue. After several closures and changes of name, the venue opposite is now called Eric’s.

The following morning we planned to visit the Roman Catholic cathedral before visiting a few of the city’s many museums. The proposal to build a Catholic cathedral in the city was the result of the influx of Irish immigrants, predominantly Catholic, who came to the city to escape the Potato Famine [1845-1852].

Several attempts to build a cathedral were made.

Initially, a design by Edward Welby Pugin [1833 – 1875] – not to be confused with his father Augustus Welby Pugin who was involved with the design of the Houses of Parliament – saw only the Lady Chapel completed between 1853 and 1856 and this chapel was used as a parish church until it was demolished in the 1980s.

After this false start, the site of a former workhouse was bought in 1930 and Sir Edwin Lutyens [1869–1944] was commissioned to design “an appropriate response” to the Anglican Cathedral already under construction nearby. Lutyens’ therefore planned to go large. His design would have become the second largest church in the world and was to have included the world’s largest dome.

Work started in June 1933 and was paid for largely by donations from working class Catholics. In 1941 work was stopped due to WWII restrictions and in 1956 work on the crypt was resumed. The crypt was eventually finished in 1958, but Lutyens’ design for the cathedral was considered too costly but this time and was abandoned with only the crypt complete.

Interestingly Adrian Gilbert Scott, brother of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect of the Anglican Cathedral, was commissioned to designed a cheaper scaled down version of Lutyens’ design. This retained the massive dome but was poorly received and was rejected.

In 1959 an international competition to design the cathedral was held with two main requirements: everyone in the 3,000 strong congregation should be able to see the altar and the Lutyens crypt was to be retained and incorporated into the design. The congregation was subsequently reduced to 2,000.

The winning design by Sir Frederick Gibberd comprises a circular building with a central altar and transforms the roof of the crypt into an elevated platform, with the cathedral standing at one end. Above the altar rises a lantern shaped like a crown with stained glass said to represent the Trinity. Above the altar is a crown-like baldacchino or canopy, designed by Gibberd and made of aluminium rods, which incorporates loudspeakers and lights.

Surprisingly, this cathedral was completed in 1967, just over a decade before its more traditionally-styled neighbour, the Anglican cathedral about half a mile to the south.

For a mere £5.00 you can go down to the Lutyens Crypt which houses the treasury and a permanent exhibition about the building of the cathedral as it is today. The word crypt conjures up an image of somewhere dark with low ceilings, but this is altogether on a different scale and, although the central area is artificially lit, huge windows do allow natural light to stream in. In fact 1,300 panes of glass are used in just one window in the Crypt Chapel. The space is so vast it is sometimes referred to as ‘Liverpool’s third cathedral’.

The exhibition explains that ‘There are seven million bricks in the crypt’s vaulted ceilings and towering buttresses’ which were intended to support a church to rival St Peter’s in Rome. A very socially aware Lutyens’ originally planned for the building to remain open day and night, its floor heated, as a refuge for the homeless. Building work slowed down during the Second World War and at one point apprentice bricklayer, 19 year-old Arthur Brady, is the only man left working in the crypt, before he too is called up. In 1941 construction stops completely for 15 years. During the war Liverpool is repeatedly bombed and the crypt is used as an air raid shelter for hundreds of local residents.

The Lutyens Crypt includes the Chapel of Relics which is separated from the main body of the crypt by a six ton rolling marble gate, similar to the stone used to close the tomb of Jesus. The rolling stone is moved with the use of a winch within the wall to its left. It was open when we visited and we weren’t the only people who wanted to see this ingenious design in motion.

We saw a couple who refused to pay to go down to the crypt, despite the nominal fee. They truly missed out: we would thoroughly recommend a visit to this hidden underground gem.

Leaving the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ, the King and walking round its grounds, you can see the extraordinary and surprising fusion of traditional and modern architecture.

From here we walked back down to the waterfront. The Liverpool docks have undergone significant regeneration and are now home to bars, cafés and several museums including the Museum of Liverpool.

This includes a section on the now dismantled Liverpool Overhead Railway which opened in 1893 and originally ran five miles between Alexandra Dock and Herculaneum Dock. It was later extended south to Dingle and north to Seaforth and Litherland. It was nicknamed the Dockers’ Umbrella as they could walk along underneath it and keep dry on their way to and from work. The railway could boast had a number of world firsts: it was the first electric elevated railway, the first to use automatic signalling and electric colour light signals and was also home to one of the first passenger escalators at a railway station.

Sadly it was closed in 1956 and, despite local protests, dismantled in 1957.

Warehouse buildings and dry docks have been retained in the regeneration of the area.

The ferry across the Mersey is famously celebrated in song and the well-known tune is played as the craft docks. We did not take a trip on it this time although Matilda was very tempted.

Instead we planned to visit The Beatles Story in preparation for our tour of both Paul McCartney’s and John Lennon’s homes the following day. This includes a wealth of information about the band as well as reconstructions of various important sites, including The Grapes [which Matilda felt was slightly redundant as you could visit the original] . . .

. . . and the stage at first The Cavern Club.

Liverpool, quite rightly, celebrates The Beatles but this makes it easy to forget some of the other famous people and bands who emerged from this vibrant city: Frankie Goes to Hollywood; Alison Steadman; Echo and the Bunnyment; Kim Cattrall; a Flock of Seagulls; Shaun Evans and Rick Ashley to name but a few.

After immersing ourselves in The Beatles Story, we set off in search of refreshments.

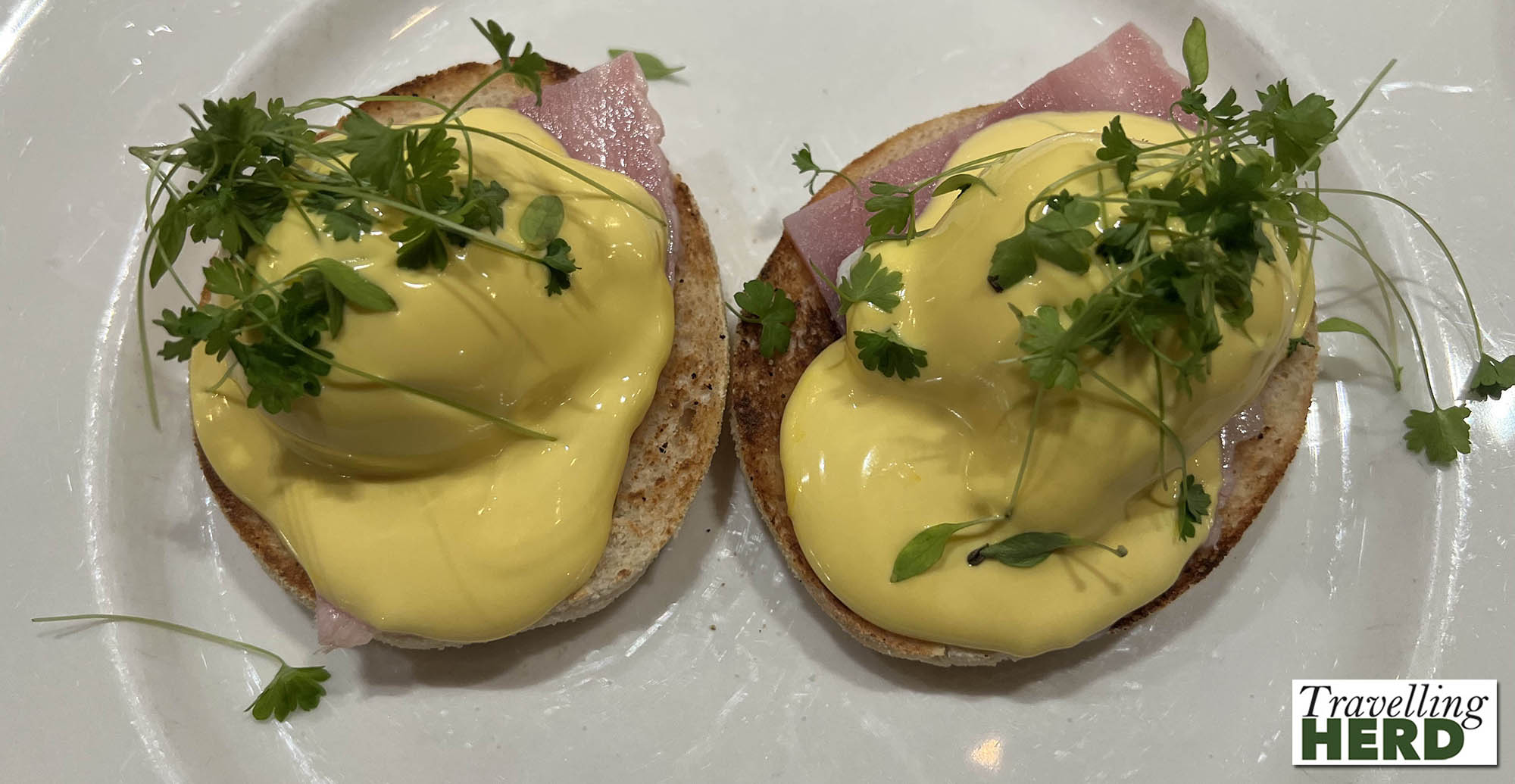

There is a Marco Pierre White Steak House in our hotel and although we did not eat there in the evening, the breakfast menu included Marco’s Eggs Benedict [see Dish of the day] which we felt we had to try. Admittedly, the hollandaise sauce was rich and velvety but we both felt we had had better versions of this elsewhere. Sorry, Marco.

Selfie of the day:

Dish of the day:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.