Read this blog: The one where Robert prefers to watch

Friday 5th April 2024

The day started well. A young boy came down for breakfast while we were eating and to amuse him, the receptionist turned on the overhead model railway, which was complete with scaled versions of the Bridge over the River Khwae. We think we were probably more excited about this than he was.

Having travelled over the bridge over the River Khwae Yai yesterday on the train, Robert wanted to go to the bridge itself to watch a train pass. He firmly believes that watching the trains is a more satisfying experience than riding on them.

There is a station on the south side of the river called the River Kwai Bridge Station [see below] surrounded by stalls selling all manner of souvenirs. We have been struggling to find a standardised spelling of Khwae/Kwai. It seems the former is usually used for the rivers the Khwae Yai and the Khwae Noi which meet in Kanchanaburi. But it also appears that the Thai’s are happy to use the Anglicised version popularised by the 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai to make things easier for the tourists. During the war, when the bridge was built, this stretch of river was known as the Mae Klong River but it was renamed Khwae Yai in 1960.

Near the station, there was the shell of a flying kampong, a type of truck manufactured by the Japanese, which could run on rails as well as roads.When it arrived at railway tracks, the road wheels were removed and the front axle could be replaced by a small pivoting bogie. Sometimes these trucks were camouflaged to look like bamboo huts and so they were nicknamed flying kampongs by the Allied soldiers, since kampong translates as ‘village’.

There are comparatively few trains per day and we had been given a timetable which very helpfully gave not only the departure time from the station, but also the time the train would be crossing the bridge. We decided we would aim to watch the 10:44 river crossing heading north to Namtok [now the end of the line].

Robert of course ensured that we arrived with plenty of time to spare. This allowed us the opportunity to take photographs from several angles.

The Thai authorities have really embraced the tourist interest in and enthusiasm for this piece of WWII history.

A walkway has been fitted over the sleepers to allow tourists to stroll along the tracks and cross the bridge more safely. Small platforms jutting out from the side of the bridge have also been added at regular intervals on either side. These act as viewing points [see above] and provide space to stand, behind the red lines, while the trains pass.

We walked across the bridge to a deserted area which may or may not once have been a prisoner of war camp.

Certainly there were several rusting army vehicles but since these were American they cannot have been genuine war relics.

Although there was no-one around, there were open air bars and food stalls with all the equipment ready to start cooking and serving food and drink. There was also a stage with a sound system set up. There is a market known as the Prisoner of War Camp Market, or the Concentration Camp Market, but this is further away from the river and the bridge so we felt this may be more of an opportunist social venue.

On the other side of the track stands the Wihan Phra Phothisat Kuan Im Temple, a buddhist temple with a decidedly Chinese influence. An imposing statue of Guan Yin, goddess of compassion and mercy overlooks the bridge which seems quite appropriate for a section of the Death Railway.

Initially a wooden bridge was built here a little further up river and finished in February 1943. In June 1943 a second bridge was erected using concrete pillars and eleven iron curved-truss bridge spans which the Japanese had dismantled and transported from Java. This was bridge 277 of the original railway.

On 24 June 1945 the RAF destroyed the bridges, putting the railway line out of commission for the rest of the war. When it was subsequently rebuilt two new angular central spans were installed.

In the time before the train is due, tourists walk freely across the bridge on the tracks and pose for photos.

When it is approaching the time for the train to pass, people take up position in one of the viewing platforms and clear the track.

The engine stops before crossing the bridge to make sure people are out of harm’s way and much use is made of the train’s horn before the train travels very slowly across the bridge. Presumably this is both to allow people to take photos and to minimise wear and tear.

Although not quite as ‘up close and personal’ as Train Street in Hanoi, it is still exhilarating to be so close as the train passes [see Video of the day].

By comparison the Kanchanaburi Skywalk is a relatively new attraction which opened in 2022.

It is 150 metres long and 12 metres high and the walkway is made of glass. To protect the surface, visitors must wear cloth over-shoes and no bags are allowed. We saw that a bird had, perhaps ill-advisedly, built a nest on the supports just below the glass. There are signs limiting the number of people in certain areas, but there are no staff to monitor whether or not this is exceeded.

The Kanchanaburi Skywalk is positioned to give people a bird’s eye view of the confluence between the Khwae Yai and Khwae Noi rivers.

From here we went to the prosaically named Death Railway Museum and Research Centre – a title which does not do this fine institution justice. The exhibits in the museum give a very clear account of the history of the railway from its conception through to its removal post war and unlike other war museums we have visited on this trip it is largely impartial and non-partisan.

In the gardens stands one of the wagons used to transport PoWs up to the railroad to the latest work site. About 28 men were forced to travel inside, locked in, sometimes for days, to get to the current construction site.

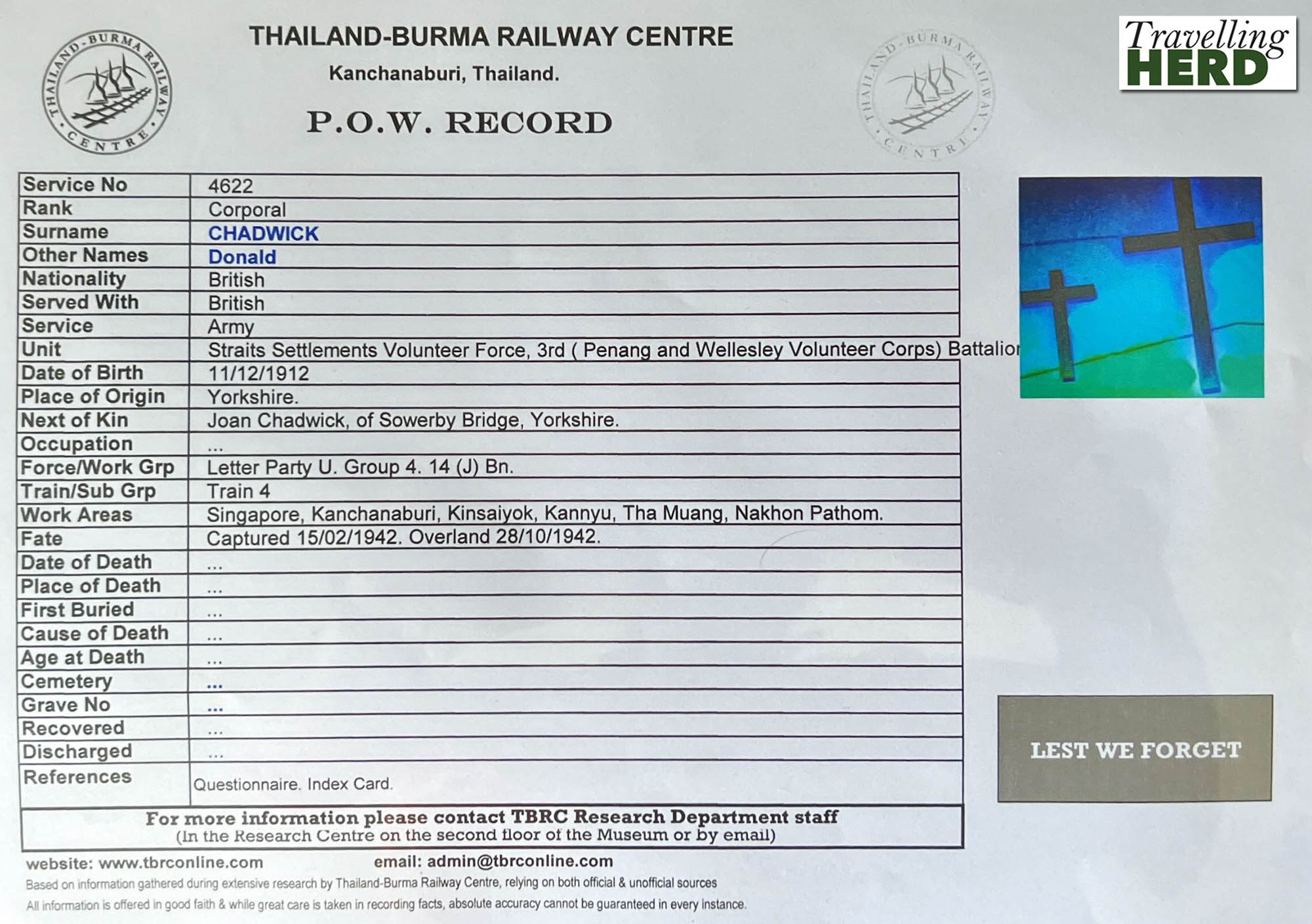

When Robert mentioned to his mother that we would be visiting Hellfire Pass, she told him rather vaguely that she had a relative who had been there. The night before we planned to visit the museum, Robert’s mother confirmed that it was her mother’s cousin who had been a PoW here. We were therefore hoping to find out any information that might be available about Donald Chadwick who was in the British Army and taken prisoner at the Fall of Singapore.

The system was very efficient. We asked at the desk and a curator took us to a workstation where we had to write down the name we wanted him to research. The PoW record promptly appeared showing that Corporal Donald Chadwick had been captured in February 1942 in Singapore and was then sent in turn to Kanchanaburi, Kinsaiyok, Kannyu, Tha Mueang and lastly Nakhon Pathom.

We now had confirmation that he was indeed sent to Konyu Cutting and was one of the men who were forced to work at Hellfire Pass. It also confirmed that he had survived the ordeal and was not buried in the cemetery here. Indeed, messaging other relatives, Robert’s uncle Richard remembered meeting Donald at a family event, but like many others it is doubtful that Donald ever spoke much about his experiences after his return. We felt privileged to be able to take a copy of his PoW Record away with us.

Opposite the museum stands Kanchanaburi War Cemetery [DonRak], one of three cemeteries for Allied PoWs who died while forced to work on the Burma-Thailand Railway. Starvation rations, hard labour and poor nutrition meant that diseases such as malaria, cholera, tropical ulcers and dysentery were often fatal. Doctors really could make the difference between life and death, particularly if the doctor had some experience of tropical medicine, as many of those who had spent time in the Dutch East Indies did.

But brutal treatment also took its toll: during the Speedo period, 69 men were beaten to death. During construction of the railway, approximately 13,000 PoWs died and were interred along its path. Records were less accurate for the civilian labourers but it is estimated that between 80,000 and 100,000 civilians also died and were often buried in mass graves. Many of these victims remain unidentified and unnamed.

The death rate of twenty men per day is equivalent to one man dying for every sleeper that was laid.

Since surrender was anathema to the national psyche, the Japanese placed little or no value on the lives of PoWs. Ironically however, the national reverence for their ancestors meant that the Japanese treated the men with more dignity dead than alive. Camp burials were held and in the early days, Japanese personnel even attended the services. Both the Japanese and the prisoners themselves kept records of the Allied deaths.

After the war, an Allied War Graves Commission survey party sought to recover the remains from the Death Railway. Their search covered the length of the railway from Thanbuzayat to Nakhon Pathom and took place between 24th September and 10th October 1945. They found a total of 10,549 graves, in 144 cemeteries on or near the railway. Incredibly, they only failed to locate 52 of the graves they knew to exist.

The Allied dead were exhumed from the burial grounds near the camps and transferred to one of three dedicated cemeteries at Chungkai and Kanchanaburi in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Myanmar. The Americans who died on the Death Railway were exhumed and repatriated.

The Kanchanaburi War Cemetery covers almost 7 acres and is the last resting place for 6,982 Allied military personnel. They lie in graves marked with small low black stones carved with their names.

Sadly records of the deaths amongst the civilian forced labour were not as accurate and many were cremated and could not be individually identified.

An obelisk at Wat Thaworn Wararam Temple now marks the spot where thousands of enslaved civilians were slain and buried after the railway was completed and they shall also be remembered.

Video of the day:

Selfie of the day:

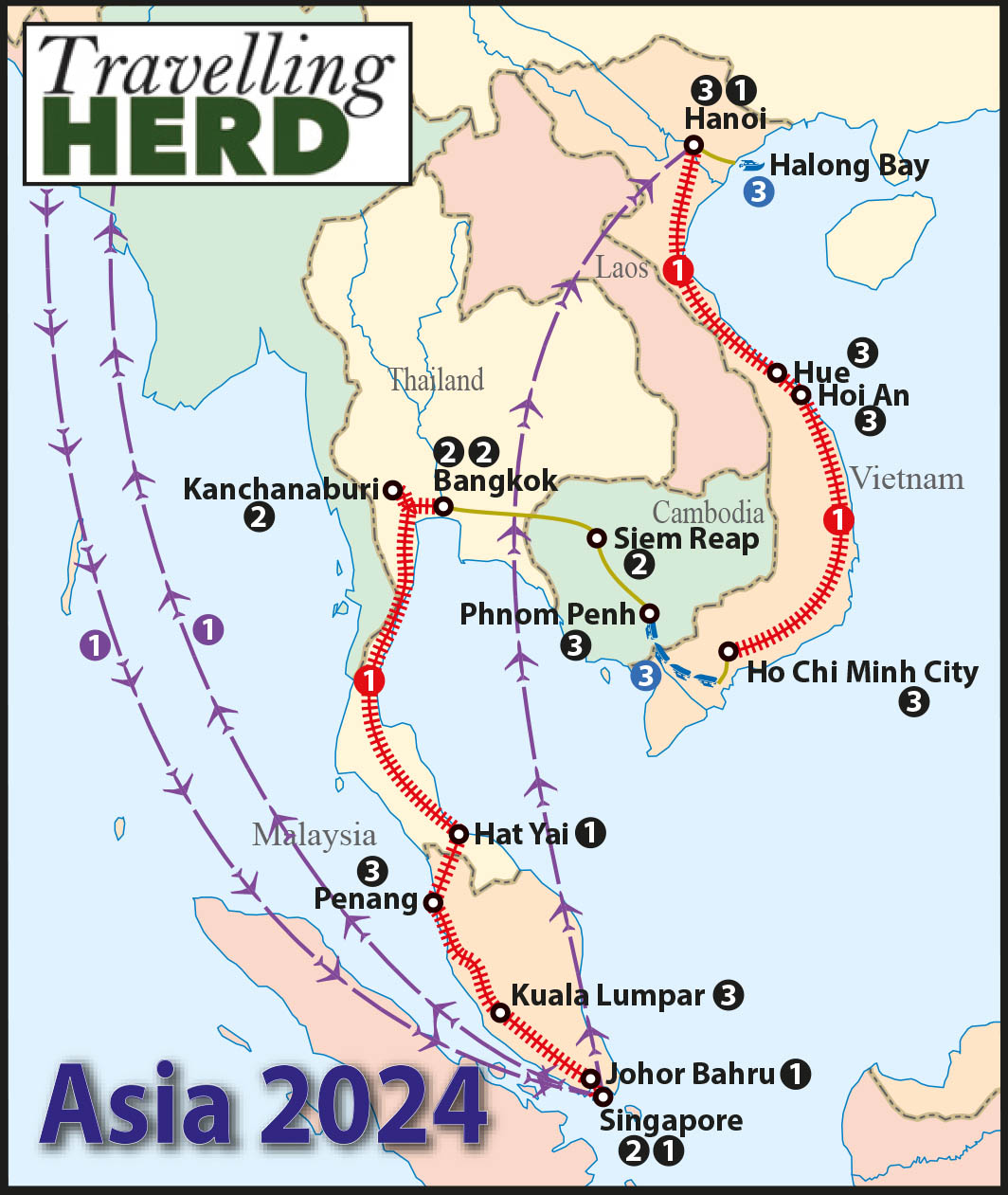

Route Map:

One thought on “Asia ’24 #24: Bridge over the river Khwae”

My father, Walter L. Beeson, was one of the USS Houston CA30 Prisoners of War who built those bridges.