Read this blog: The one where we see a hundred grains of rice move two tons of rock

Thursday 4th April 2024

Today combined two of Robert’s key interests: railways and WWII: its impact and legacy.

As early as 1885 the British government had undertaken a survey to assess the feasibility of building a railway line linking Burma and Thailand. However, the route would have passed through steep jungle terrain and crossed many rivers. The project was judged to be too difficult and was abandoned.

Over fifty years later towards the end of 1941, the Japanese invaded Thailand and then advanced into Burma in early 1942 in preparation for launching an attack on Singapore in February of the same year.

The shipping route from Japan to Burma around the Malay Peninsula was 2,000 miles long [3,200 km] and was vulnerable to Allied submarine attack. An overland route was needed to ensure that supplies reached the Japanese Army in Burma. When Singapore fell, the Japanese took 110,000 Allied Prisoners of War [PoWs]. This was almost an alien concept for the Japanese who adopted the bushido warrior code which demanded death before surrender. Eventually it was decided that PoWs could be put to use to support the Japanese war effort. Some were held in Singapore whilst others were shipped to Japan and thousands were transported to Burma and Thailand to build the Burma-Thailand Railway.

Civilian labourers from the invaded Asian territories were also forced to work on the railway. Referred to as Romusha these civilians lacked the organisation of the PoWs and had even less access to medical help: the death rate amongst the Romusha was consequently higher than among the PoWs.

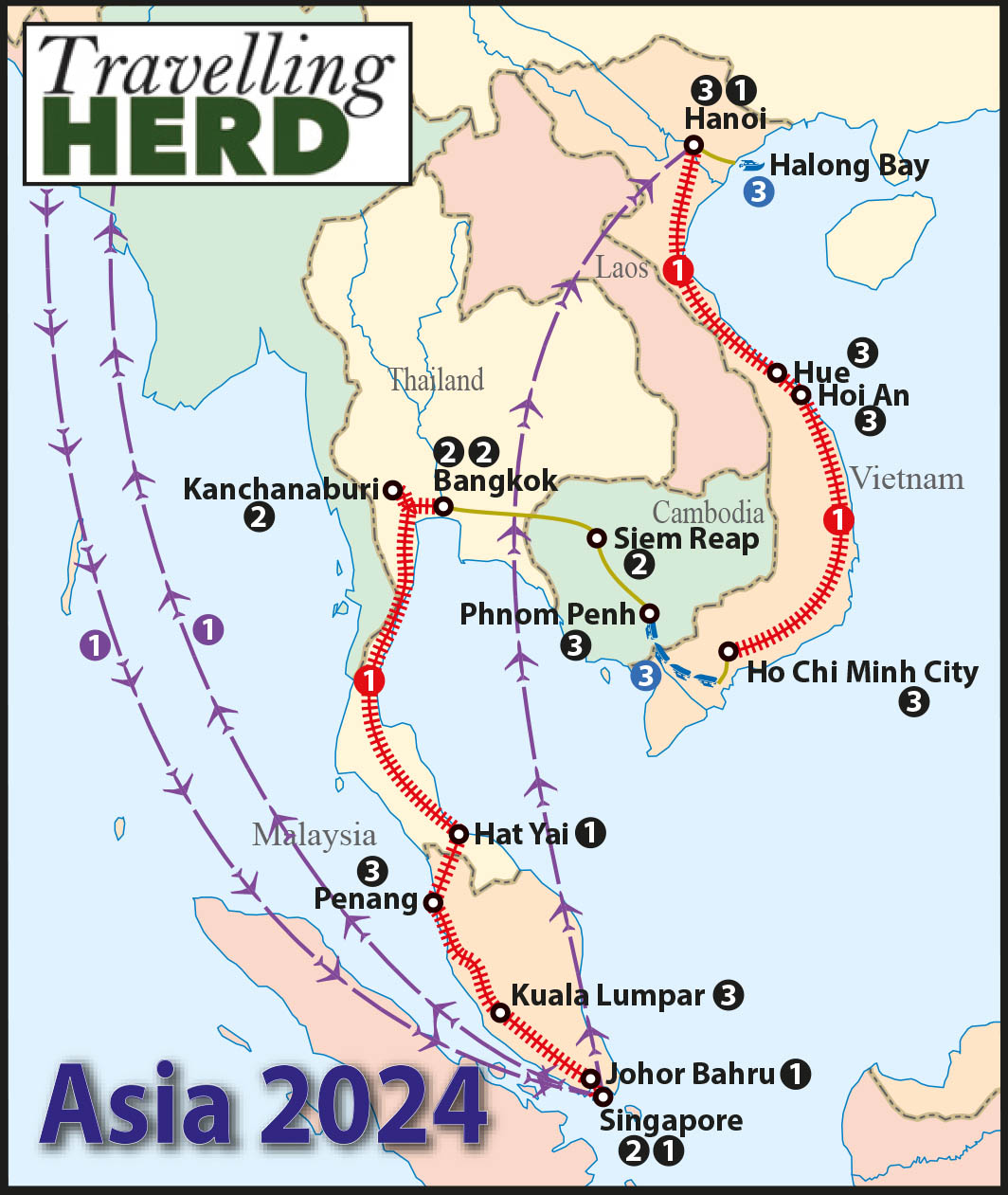

We hired a taxi for 1,700 Thai baht [£35] to drive us the 45 miles to take us to the Hellfire Pass Interpretive Centre where the museum, walkway and memorial now honour all those who worked on the railway: American, Australian, British and Dutch Prisoners of War as well as conscripted nationals from Burma, Malaya and Thailand.

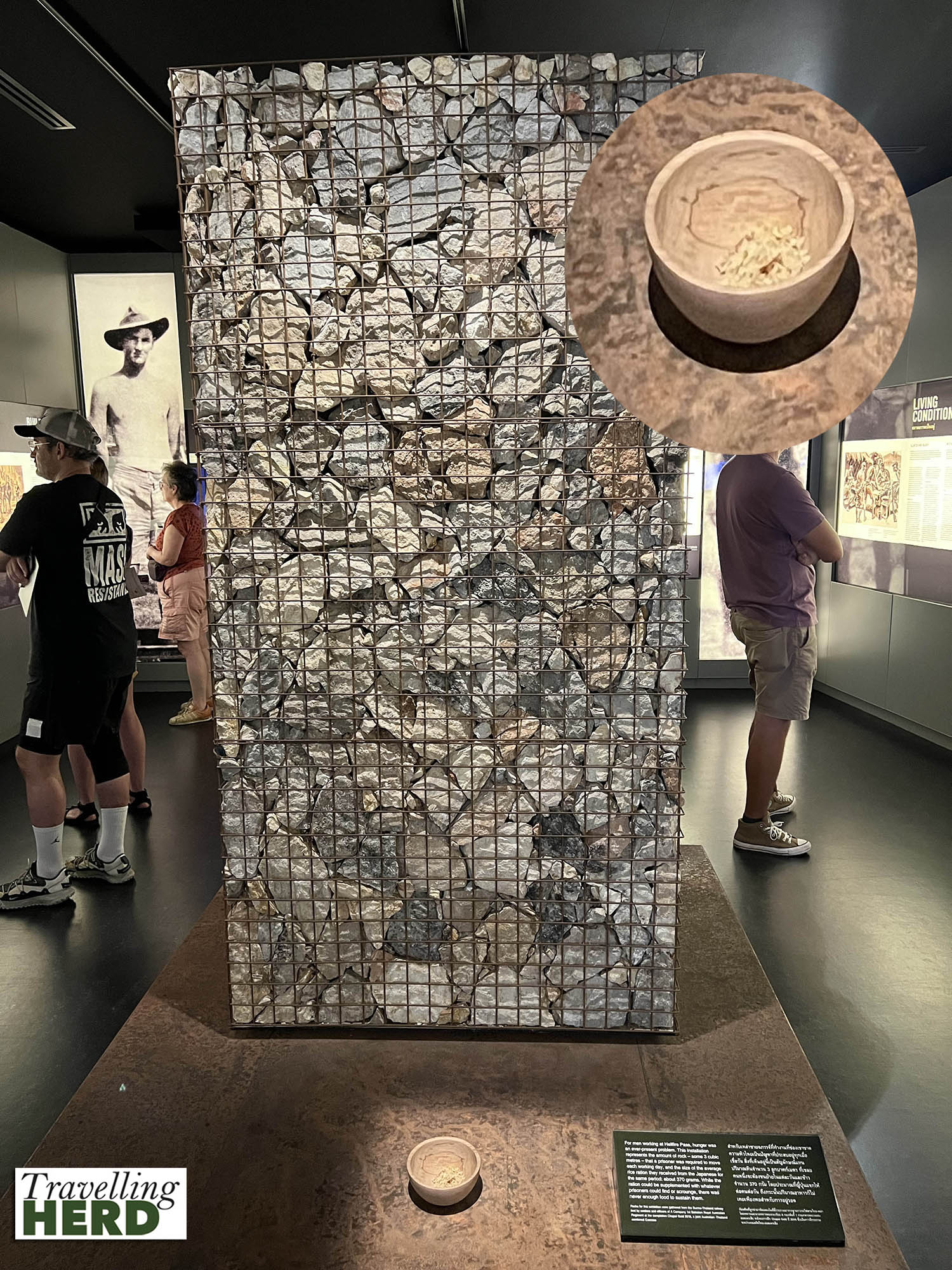

Conditions were so bad that it became known as The Death Railway. One exhibit in the Hellfire Pass Interpretive Centre graphically demonstrates the extraordinary demands of the Japanese captors. The rice in the bowl is equivalent to one day’s food ration for the PoWs who were expected to move the amount of rock contained in the wire cage every day.

The day we visited the temperature rose to 41°C.

The view from the start of the walkway is now deceptively rural and picturesque.

There is an audio guide explaining various sights as you walk along the track bed from the Hellfire Pass Interpretive Centre, choosing one of two possible routes.

The first walk takes visitors down to the memorial obelisk and back. This is the shorter option and takes about 50 minutes. Visitors are advised to take water and apply insect repellent.

The second option carries on past the memorial down to Hintok Cutting and includes steep climbs and descents. One of the most famous trestle bridges was built on this stretch: Hintok Bridge was called Pack of Cards Bridge because it collapsed three times before it was completed. Walkers are told to allow about three hours for this route and have to take a safety radio with them as well as plenty of water and insect repellent.

In cooler weather we might have chosen the longer walk and opted to be collected by our taxi at the bottom but in the extreme heat we opted for the short walk and set off with our water but no radio.

This rock cutting in the Tenasserim Hills was one of the most difficult and deadly on the whole route: Konyu Cutting was the largest one on the line [see also the feature photo] and was built in a remote area using predominantly hand tools.

A short length of track marks the start of the cutting. It was part of the original railway and was relaid in 1989 by the men of the ‘C” Company 3rd Battalion Royal Australian Regiment then relocated here in 2006.

As the war progressed and the Japanese suffered various defeats, Tokyo demanded that the Japanese engineers speed up construction of the railway. What became known as the ‘Speedo’ period was implemented and for twelve terrible weeks from July to October 1943 men worked round the clock. The light of the bamboo fires and oil lamps shining deep in the cutting as the sick and starving men worked look like a scene from Hell and gave rise to the name Hellfire Pass.

The excavation work was largely done by hand without the aid of reliable mechanical equipment. Although compressor drills were brought during the Speedo period, they proved unreliable. Men would use hand tools to make holes large enough to hold dynamite, then retreat for the blast.

A tipper truck still stands on a small stretch of track above the cutting. The stone and rubble created by blasting was carried up out of Hellfire Pass and loaded into tipper trucks to be thrown over the hillside.

The obelisk was built by the Office of Australian War Graves and stands in a clearing as a memorial to all the thousands of lives so tragically sacrificed in the construction of the Burma-Thailand railway. It also honours the Thai people who risked their lives to supply medicines and food to the prisoners during those dangerous times.

Of the 258 miles [415 km] of track on the Burma-Thailand Railway, 69 miles [111 km] were built in Burma [now Myanmar] and the remaining 189 miles [304 km] were in Thailand. Construction started in both countries and the track was finally joined at kilometre 263, about 11 miles [18 km] south of the Three Pagodas Pass.

The completed railway was functional from October 1943 to June 1945 with occasional interruptions caused by bomb damage.

Having walked back up to the Hellfire Pass Interpretive Centre our taxi took us to Namtok Station, which is the now the end of the line. From here we would travel by train back along the section of the Death Railway which is still operating and over the Bridge over the River Khwae to Kanchanaburi.

The route runs beside the Kwae Noi River for part of the way.

The vegetation is lush and green.

In places the drop is sheer to the riverbank.

The track passes over a wooden trestle bridge, called the Wang Pho Viaduct, perched precariously between the river and the sheer cliffs. The trains go very slowly across this section and some passengers board just for this small stretch.

Consequently, there are a lot of souvenir shops and riverside cafés and bars here. You can also glimpse a rock cave here which was used by the Japanese when the railway was being built.

Further on, tourists stand and watch as the train crosses the Bridge over the River Khwae Yai [see Video of the day].

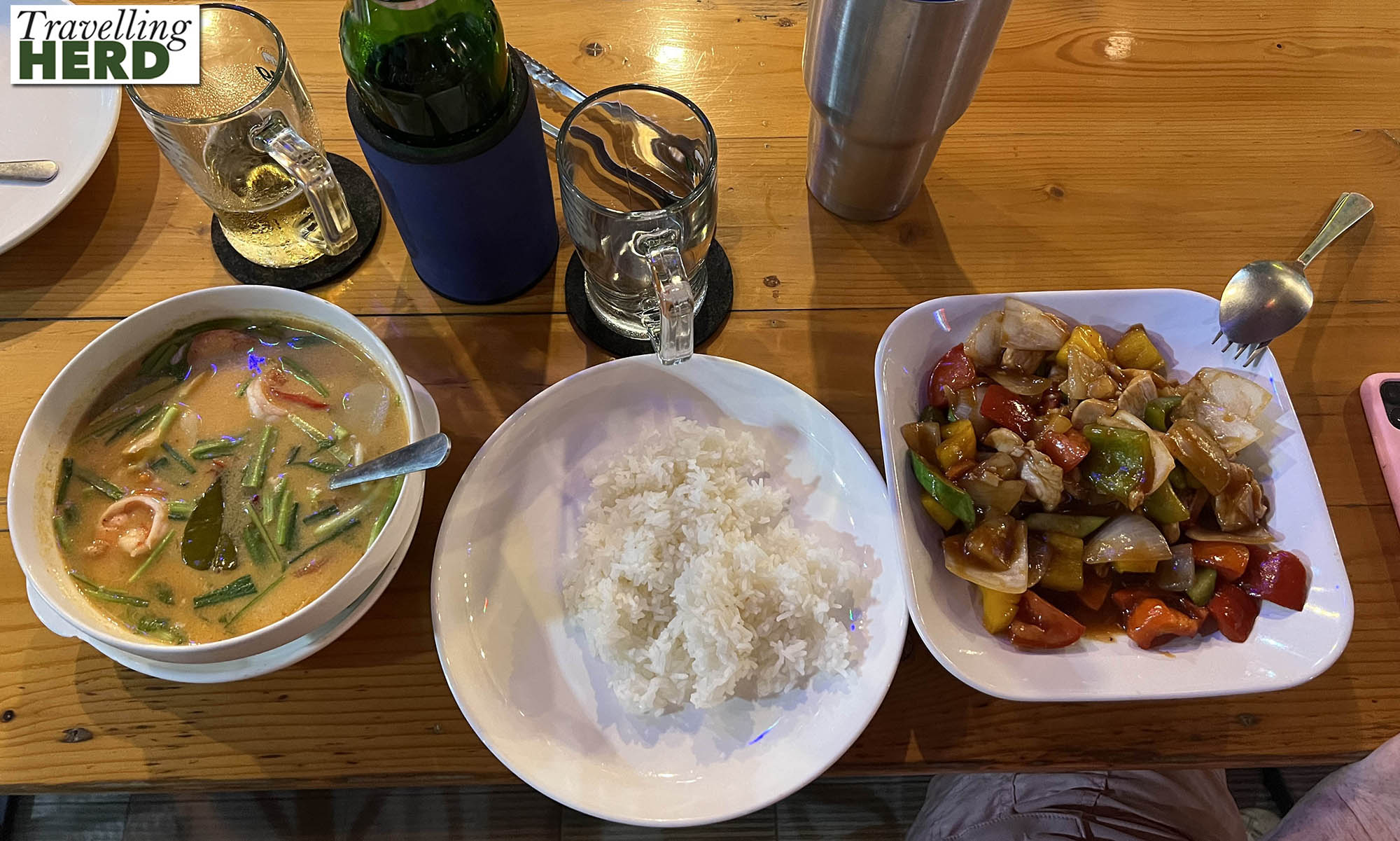

After an emotional day, we returned to the same bar where once again we saw the pick up truck with the dogs drive past, chased by the more energetic pack member. It is obviously a regular occurrence. Robert opted for another traditional local dish: Tom Yum Soup.

Video of the day:

Selfie of the day:

Dish of the day:

Route Map:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.