Read this blog: The one where we visit an Imperial Citadel

Saturday 9th March 2024

The Imperial Citadel of Thăng Long is an extraordinary mixture of historical buildings, archeological excavations and twentieth century wartime command bunkers. It was the centre of power for eight hundred years.

From here first the Chinese administrators and later the Vietnamese Emperors ruled. More recently, the headquarters of the North Vietnamese government and army were located here during the period which the Americans refer to as the Vietnam War (1955-1975) but which is also called the Resistance War against America; the Second IndoChina War; the American War in Vietnam and we also heard a guide call it the Civil War.

The entrance to the Citadel was lined with lanterns, although these may have been left over from New Year celebrations rather than being permanent, and the trees were carefully trained on trellises to resemble parasols.

Construction of the Imperial Citadel of Thăng Long was started in 1010. The gateway certainly evokes centuries of history. The five gates served as entrances for different classes of people, with a strict hierarchy and the central gate was reserved for the emperor and the two either side for mandarins.

The Imperial Citadel of Thăng Long was constructed with three rings of fortifications protecting one another, which were respectively named the Dai La Citadel, Imperial Citadel and Forbidden Citadel. In between these fortifications, the Lÿ, Trân and Lê dynasties built palaces, pavilions, towers, pagodas, temples and shrines, which served as the working and residential quarters for the royal family and imperial court.

Sadly, when Hanoi was controlled by the French as the capital of Indochina (1885–1954), the Citadel was largely demolished to make way for offices and barracks so what remains is the main south gate and the Flag Tower [see blog Asia ‘24 #2].

However, an extensive excavation is underway to discover more about what lies below this unique site and some areas where the archaeologists are working are screened off.

As you walk further into the Citadel, the crowds thin out and you come to Bunker House D67. This is an unassuming, single storey building but it was constructed with 60cm thick walls and is soundproofed as befits a military command centre. The roof also incorporates a layer of sand to prevent shrapnel breaching the structure.

D67 was constructed in 1967 at the height of the American War [Vietnam War] on the northern part of the palace foundations. It housed the General Headquarters of the People’s Army of Vietnam and contained meeting rooms for the Politburo, the Vietnamese Communist Party’s policy-making committee. General Vo Nguyen Giap, the then Minister of Defence and Vietnam’s most famous modern military figure, and General Van Tien Dung, Chief of the General Staff, both had offices here.

Hidden within is a deep bunker, 9m underground, accessible both from the building and from the former French artillery headquarters. There are two doors, like an airlock, and the outer one is made of 1cm thick steel. The meeting room seems ready to host another session.

Close by is the Hau Lâu which was one of the houses for the king’s concubines in the harem area of the Citadel.

The staircases and the splendid dragon-shaped handrails which led up to the Imperial Kinh Thiên Palace were constructed in 1467, during the reign of King Lê Thanh Tông and survived the French demolition of much of the site.

A shrine now stands at the top of them. Behind this shrine, excavation is underway where the palace once stood and the French buildings which supplanted it have been shrouded in a decorative yellow scaffolding cover.

A second bunker under the Imperial Citadel of Thăng Long, known as the T1 bunker was built in late 1964 when U.S. troops were spreading further into northern Vietnam and served as the Military Operation Bunker of the General Staff.

The T1 bunker covered 64-square-meters (689-square-foot), and was equipped with a steam-powered air conditioning unit, ventilation and electromagnetic interference systems. The steel-plated door was designed to protect those inside from bombs, radioactive rays and poisonous gas.

The Vietnamese are rightly proud that at different times in their history they defeated not only Imperial China and France but also the superior firepower of the American armed forces from these bunkers.

From the Citadel we walked to Quan Su Pagoda, where locals pray for good luck. The current building dates from the 15th century. It was previously known as the Ambassadors’ Pagoda as there was a guest house for foreign envoys close by and since the majority were Buddhist, many of them worshipped here.

Matilda was most impressed that the offerings at one of the shrines included a very neat pyramid of beer.

We continued on towards Hoàn Kiếm Lake where the Turtle Tower stands isolated on a small island. According to legend, during the war against the Chinese Ming Dynasty in the early 15th century the Golden Turtle God gave King Le Thai To a precious fairy sword. In 1427, after 10 years of conflict and struggle, the Chinese were finally defeated and Vietnam reclaimed its independence. That same day, a large turtle came to the King, who was boating on the lake, took the sword and vanished beneath the water with it, much like the Lady of the Lake in Arthurian legends. The King built the temple and renamed the lake Hoàn Kiếm Lake or Lake of the Returned Sword.

We walked on to Tràng Tiền Plaza, a shopping centre which was built to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the liberation of the south of Vietnam. Construction began on April 30, 2000 and the complex took 18 months to complete. We planned to return to shop another day.

The neoclassical Hanoi Opera House was erected by the French colonial administration between 1901 and 1911. Unsurprisingly, the nearby Hilton Hanoi Opera Hotel which opened in 1999 was not named simply the Hanoi Hilton as this was the name given to the Hỏa Lò Prison, originally used by the French but later by the North Vietnam to house US PoWs during the American War in Vietnam.

At the weekend, the road beside the lake was closed to traffic for people to promenade and toy vehicles were lined up for parents to rent for their children to ride on.

The brutalist Martyrs Monument by Hoàn Kiếm Lake is dedicated to those who died for Vietnam’s independence.

Close by, the entrance to Thê Húc Bridge is flanked by a decorative tiger and a dragon.

Thê Húc Bridge, literally Welcoming Morning Sunlight Bridge, is a footbridge over Hoàn Kiếm Lake leading to the Ngoc Son Temple [see also Selfie of the Day].

The Thăng Long Water Puppet Theatre is also situated at this end of the lake. It has a distinctive art deco style front with puppets on display in a tower, but Robert did not feel he needed to watch a performance.

Instead having walked 9.4 miles we felt justified in going in search of liquid refreshment and some food.

Selfie of the day:

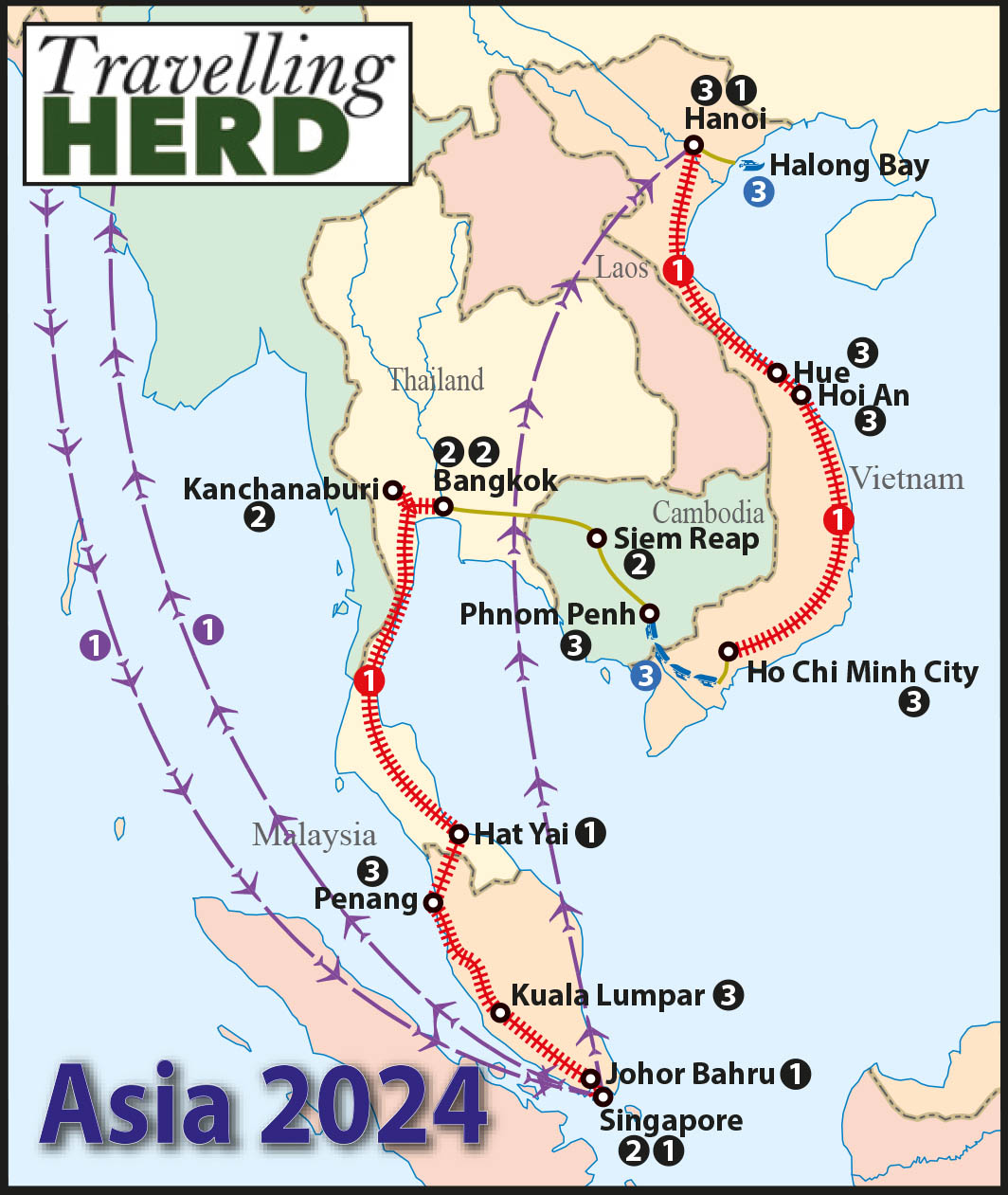

Route Map:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.