Read this blog: The one where we discover we are in two time zones at once

Wednesday 21st February 2024

The SS Great Britain was the first vessel of its kind but nevertheless she had a rather checkered history, including running aground off Northern Ireland and bankrupting her owners. Over the course of 90 years at sea she had several adaptations and she spent a further 84 years in the Falkland Islands where she was used variously as a warehouse, a quarantine ship and a coal hulk before being scuttled.

In 1970 she was bought and rescued by the owner of Wolverhampton Wanderers and, although she was close to breaking in two, sufficient repairs were made for her to be re-floated and towed back north through the Atlantic to the UK, where she returned home to the Bristol dry dock where she was built.

This former luxury passenger steamship is now a museum. The exterior of the SS Great Britain has been restored to show how she would have looked at her launch in 1843 while below deck she has been renovated to reflect some of her various incarnations.

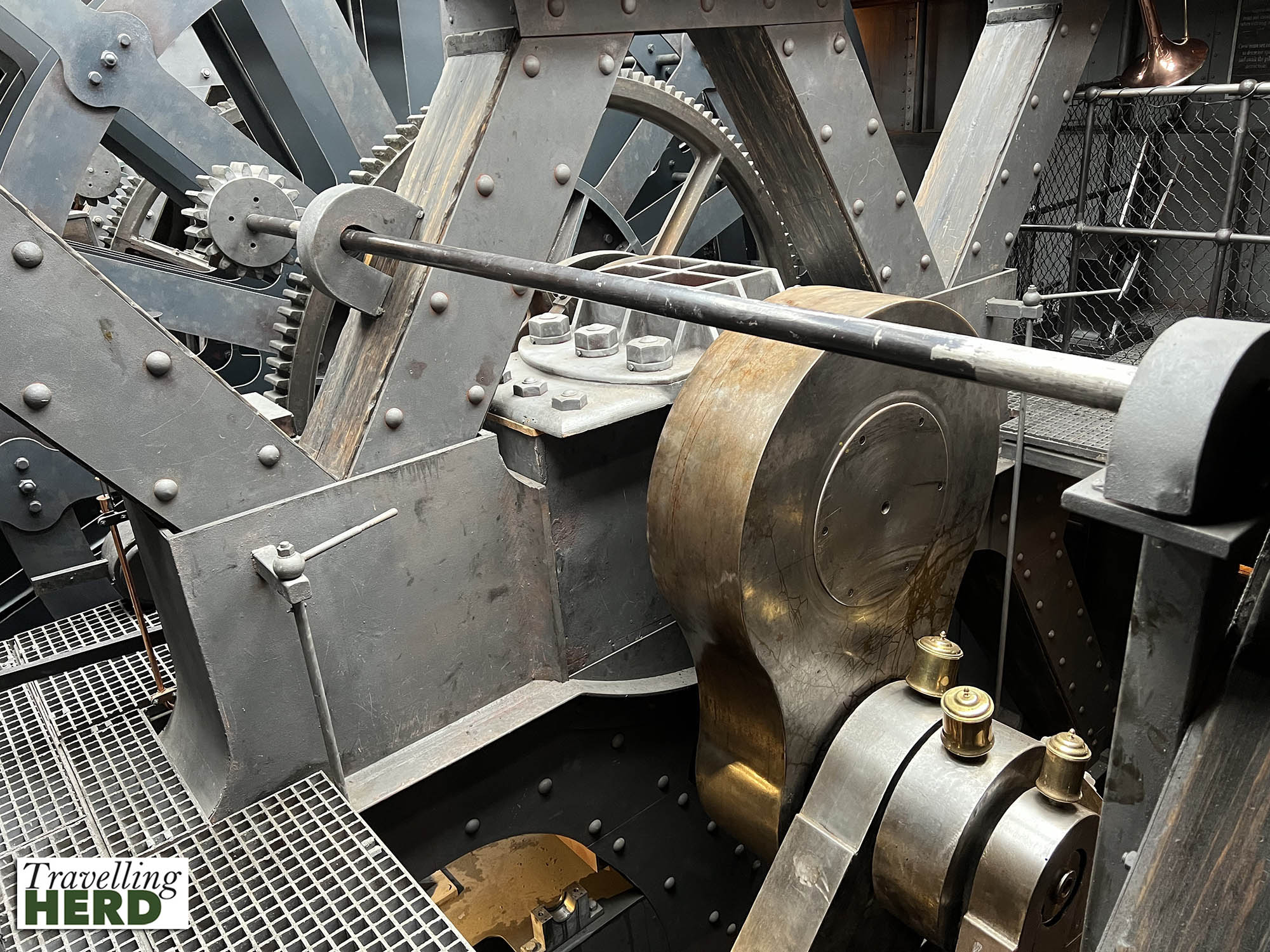

Designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, SS Great Britain was the first ship to be both built of iron and be fitted with a screw propeller which in turn was driven by the most powerful engine yet used at sea [see Video of the day, below]. Ironically, she was initially conceived as a wooden paddle-steamer but during her construction Brunel went twice to the company directors to secure approval for these major [and expensive] changes.

At the time of her launch she epitomised the latest innovations in maritime technology and was described as ‘the greatest experiment since the Creation’ which seems quite a bold claim.

She was deemed the largest passenger ship in the world between 1845 and 1853.

The SS Great Britain was the first iron steamship to cross the Atlantic Ocean, and she completed her maiden crossing in 14 days 21 hours in 1845.

Initially she was fitted out as a luxury passenger ship and although the sleeping quarters were far from spacious, the First Class Dining Saloon at the stern of the ship has been returned to its former glory. Once admired by Queen Victoria, you can now book to have Sunday lunch in these opulent surroundings.

Fine dining required a suitable galley for food preparation.

As you walk from the stern to the bow of the ship you travel forwards in time.

She was adapted to accommodate less wealthy passengers and these areas are significantly less luxurious and offer little or no privacy.

The website states that the museum offers “hundreds of sights, sounds and smells to explore”. Indeed both Liz and Robert pushed on a door which was slightly ajar only to be told in no uncertain terms to leave the occupant alone. The odour of latrines and unwashed passengers in this part of the ship was very convincing.

During her working life, she carried many interesting passengers. For the first time, people could go on holiday to Australia although the journey took 60 days. In 1861 the first All-England cricket team to play in Australia travelled there aboard the SS Great Britain. There was not enough space to practise cricket skills on board, but it is said that they played deck-quoits instead, and went on to win nearly every match on the tour. Anthony Trollope wrote the whole of his novel Lady Anna during his return voyage from Australia in 1871.

Nevertheless, in 1882 she was converted into a sailing ship. The engine and funnel were removed and three masts with square sails were installed to power her. She consequently had more cargo space and was cheaper to run. In this format she was used as a super-sized sailing cargo ship. At different times the ship carried gold-diggers, consumptives, a magician, a bishop, an organ-grinder, nuns and soldiers.

She also transported bird shit. As we drove in to Bristol, we slowly realised that we had driven along these roads before and subsequently chatting with Martin we realised that we had driven through when we visited the National Trust property Tyntesfield and the Bath Christmas market. The Gibbs family, who owned Tyntesfield also bought the SS Great Britain after she ran aground and they amassed at least part of their considerable wealth by exporting passengers and goods and importing guano.

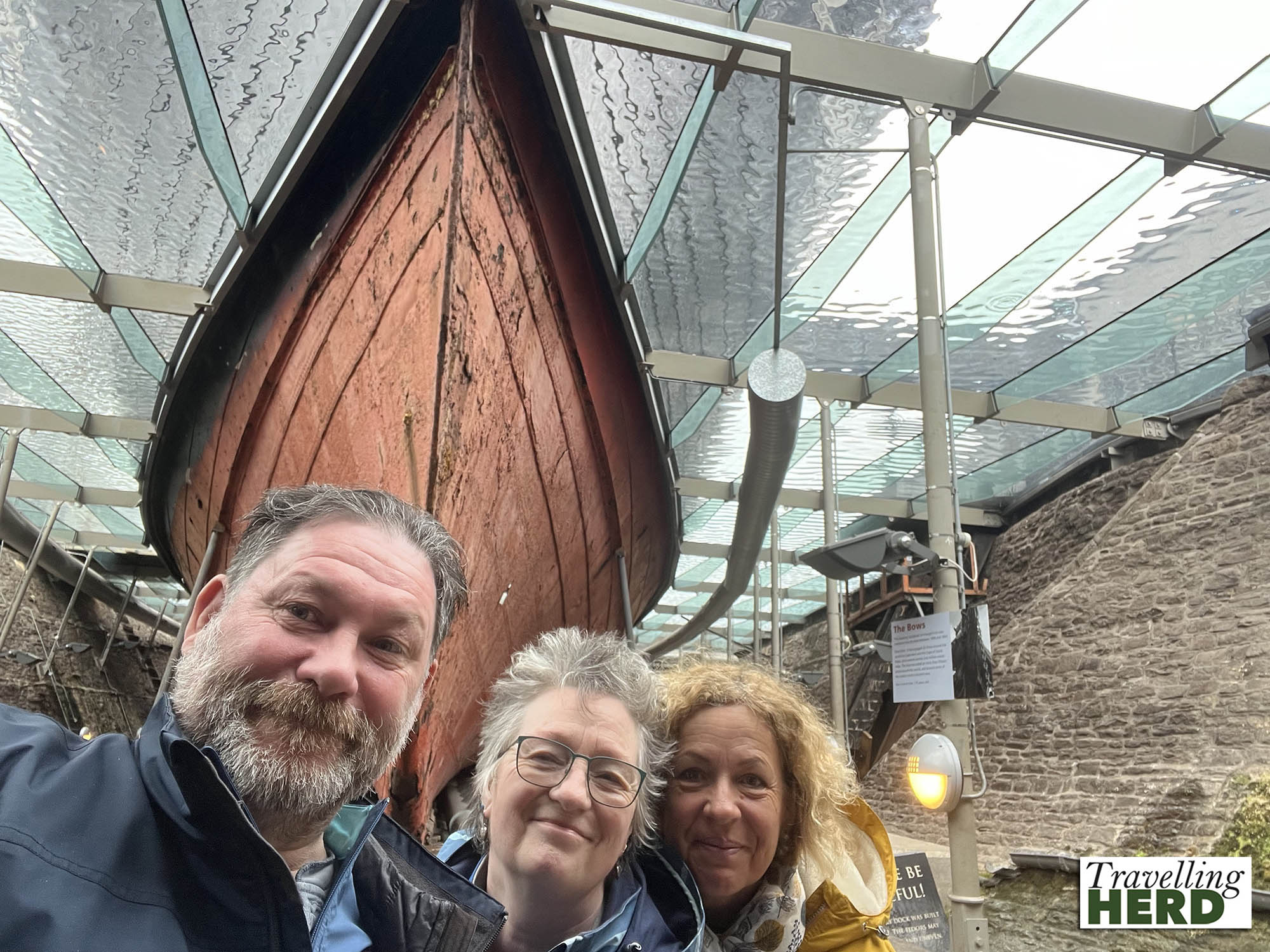

The museum also takes you below the waterline into the dry dock itself [see Selfie of the day]. A glass ceiling with a shallow covering of water creates the impression that she is floating but you can still see the some of the holes where she was scuttled in the Falkland Islands.

The restoration includes a replica of the original six-bladed propeller designed by Brunel which proved to be totally unsatisfactory in practice and was quickly replaced with a four-bladed model.

The SS Great Britain is certainly as beautiful below the waterline as she is above with sweeping curves rising up from the keel.

There is also an extensive exhibition about Isambard Kingdom Brunel himself, entitled Being Brunel. He was a driven, workaholic engineering genius. His projects include not only the steamships Great Britain, Great Eastern and Great Western, but the Clifton Suspension Bridge and the Great Western Railway. Early in his career he worked on the first tunnel under the Thames with his father. In just five months, he also designed, built and assembled a portable pre-fabricated field hospital for Florence Nightingale in the Crimea. Any one of these accomplishments would have given him a place in history.

His magic skills were perhaps a little less successful: in 1843 while performing a trick to amuse his children Brunel accidentally inhaled a half sovereign coin, which became lodged in his windpipe. Attempts to remove it with forceps failed and he was eventually strapped to a board and turned upside down, successfully loosening the coin.

From here we arranged to meet Martin for lunch in the café at the Arnolfini gallery before continuing our exploration of Bristol in the rain. We strolled round the stalls under the cover of the glass arcade at St Nicholas Market, established in 1743.

Exiting the market on to Corn Street you pass through an archway under the Corn Exchange Clock. Before 1880 there was no standardised time across the British Isles and every city had its own local time, measured by the sun and signalled by the tolling of the church bells. When people spent most of their lives close to home, this did not pose a problem but the introduction of the railways encouraged people to travel further afield.

A sign explains:

Bristol lies 2 degrees, 36 minutes west of the Greenwich Meridian and so the sun reaches its noon nearly peak 11 minutes later than in Greenwich. . . If you wanted to catch a train at noon from Temple Meads you had to remember that it would pull out at 11:49 Bristol Time. To help Bristolians catch their trains, Bristol Corporation arranged for the main public clock on the Corn Exchange to show both local and Greenwich Mean Time (Railway Time) with two minute hands.

It was not until September 1852 that Bristol adopted GMT and Bristol time and London time synchronised, but the Corn Exchange clock has retained its two minute hands. The red minute hand tells Greenwich Mean Time whilst the black hand is still set to Bristol time.

From here Robert plotted a route to the Art Nouveau Everard Printing Works which was built in Broad Street in 1900. The decorative facade is by William James Neatby who was the chief designer for Doulton and Co. [later Royal Doulton].

Three tiers of arches are surmounted by a woman holding a lamp and a mirror to symbolise light and truth. The facade also honours the contributions to printing made by Johannes Gutenberg and William Morris. It is now part of the Clayton Hotel, which opened in 2022. When the printing works were demolished in 1970 the facade was preserved as it is the largest decorative Doulton Carrara ware tile facade of its kind in Britain. The name derives from the fact that the tiles resemble Carrara marble from Italy.

Robert was particularly pleased to spot The Strawberry Thief opposite, an bar offering a fine array of Belgian beer but as it was not yet opening time we continued on to the Christmas Steps. This is a quaint historic street featuring many independent shops and leads up to the Three Kings of Cologne Chapel within Foster’s Almshouses on Colston Street. The nativity scene depicted in the stained glass in the Chapel may, or may not, be the origin of the name.

From here we continued on towards Banksy’s Queen Ziggy which appeared in 2012 for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. Originally it appeared alone on a blank wall but this has now been used for more street art. The artist can be assured that their work will appear in many photographs. Queen Ziggy is next to the offices of The Grand Appeal, a community charity supported by two well known local characters which raises money for the Children’s Hospital.

Matilda had read about a bank which had been converted into a bar and restaurant with stunning interiors. We were not disappointed when we dropped in to the rather misleadingly named Cosy Club to have a reviving drink.

She was also interested to see the Llandoger Trow, an old inn dating from 1664 which is said to be the inspiration for the Admiral Benbow Inn in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. It is also claimed that Daniel Defoe met Alexander Selkirk here. Selkirk asked to be left on an uninhabited island when he deemed the ship he was travelling in to be unseaworthy. He was proved right when the ship foundered and he was marooned for four years and four months, providing the model for the character Robinson Crusoe.

Video of the day:

Selfie of the day:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.