Read this blog: The one where we visit a genocide site

Thursday 28th March 2024

It is quite unsettling to be repeatedly accosted on the street by smiling tuk tuk drivers asking enthusiastically “Killing Fields? Killing Fields?” as though you will be in for a real treat. Although we were ambivalent about visiting, we felt we could not ignore such a defining part of Cambodian history and arranged a tuk tuk to transport us to and from the Choeung Ek Genocidal Centre. It is difficult to know what to say about something so terrible but the Cambodians themselves are very open about the genocide. Tourists are encouraged to visit the site with the aim of ensuring that it can never happen again.

The Choeung Ek Genocidal Centre and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum [formerly known as the S-21 prison housed in two former schools] are the only two sites so far which have been turned into museums detailing the crimes of the Khmer Rouge regime under Pol Pot. There are however several smaller local memorials including the former M-13 prison.

Choeung Ek lies about 11 miles south of Phnom Penh city centre and is a former orchard and Chinese cemetery. It became perhaps the most well-known of around 300 such killing fields in Cambodia which were used by the Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979 to murder, at a conservative estimate, at least a million of their own people. The exact number is unknown but is estimated at between 25% and 30% of the total population.

The price of entry is $6 per person and this includes a thoughtful and informative audio guide.

The majority of the prisoners held at the S-21 prison, now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum were eventually transferred to Choeung Ek overnight by truck. They were told they were going to a new prison due to overcrowding but once they arrived they were kept in a wooden shed where the noise of generators and loud music broadcasts masked the sounds of the slaughter happening in the nearby fields.

Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge was in power for three years, eight months and twenty days. Some historians believe that the extensive bombing of the country by the US Airforce during the Vietnam War coupled with a visit to the Khmer Rouge by King Sihanouk significantly boosted recruitment in rural areas.

Within days of taking power all the cities were emptied and the people were forced to move to the countryside into agricultural communes where the aim was to create a self-sufficient agrarian society. This involved destroying state institutions such as schools, pagodas, manufacturing and industry. Intellectuals, professionals and monks were killed and religion was forbidden. Normal human familial relations were broken to be replaced by loyalty to the anonymous “Angkar” – the Organization. The country was also closed to foreigners so news was slow to reach other countries.

The site is essentially a series of areas, now cordoned off, which were each the site of a mass grave. The bodies of 8,895 victims were exhumed here after the regime fell.

In the rainy season, the earth gives up yet more reminders of the atrocity which this land has witnessed: fragments of bone and scraps of material will rise to the surface as the floods recede and the soil moves and settles. Visitors are asked not to disturb any such relics out of respect for the dead.

Walking further round the site, we came to the chankiri tree or killing tree which is now covered in woven bracelets, like friendship bracelets, placed there by people we suspect both as an apology and as a memorial. The explanation on the audio guide made us feel sick. This was where the Khmer Rouge took babies and young children by their ankles, to ensure sufficient momentum, and swung their heads against the tree, before also killing the mothers. This was to ensure that the children would not grow up to seek revenge.

The Khmer Rouge were only ousted when Vietnam invaded in 1978. It was a source of deep shame to us that the west continued to support the Khmer Rouge long after news of the atrocities began to emerge. Indeed, inconceivably, the international community supported the Khmer Rouge holding its seat at the UN until 1993, long after its crimes had been proven.

The Buddhist stupa at Choeung Ek is visible as soon as you walk in but the guided audio tour takes you around the site first and finishes at the memorial. Robert did not want to enter but Matilda felt that she should go inside.

It contains over 5,000 human skulls, as well as other bones and some of the weapons used the kill the victims. Many of the skulls have shocking holes in them as the victims were usually bludgeoned using pick axes or hammers to conserve precious bullets.

It was noticeable that our tuk tuk driver made no effort to engage us in cheery conversation after the visit, realising perhaps the need for some time for quiet contemplation before continuing with our day.

Phsar Thum Thmei translates as “New Grand Market” but is referred to as the Central Market. It is a fine bright yellow art deco building which was built on drained marshland and completed in 1937. The 26 metre high central dome has four tall, arched hallways leading off at ninety degrees to each other. Outside, the angles between these hallways have been infilled with stalls shaded by umbrellas and awnings. Almost everything anyone could want is on sale here, somewhere.

From here we walked to Wat Ounalom, or the Ounalom Pagoda, one of Phnom Penh’s five original monasteries.

Built in 1422 it stands by the Tonle Sap River.

Its chief claim to fame is the possession of a hair from Buddha’s eyebrow which is referred to as ‘ounalom’. At present, the eyebrow hair is being carefully conserved in a building situated behind the main temple. The decorations around the entrance we think were in preparation for a wedding.

Nearby on Sisowath Quay Street they seemed to be preparing for the forthcoming Khmer New Year. The boulevard is a popular place to promenade as it runs for 3 km along the confluence of the Tonle Sap and Mekong Rivers.

After a stroll down the promenade, we returned to the roof top of our hotel to cool down and admire the view. We also decided to eat there [see dish of the day].

Perhaps the Silver Pagoda was illuminated because the King was back in residence.

Video of the day:

Selfie of the day:

Dish of the day:

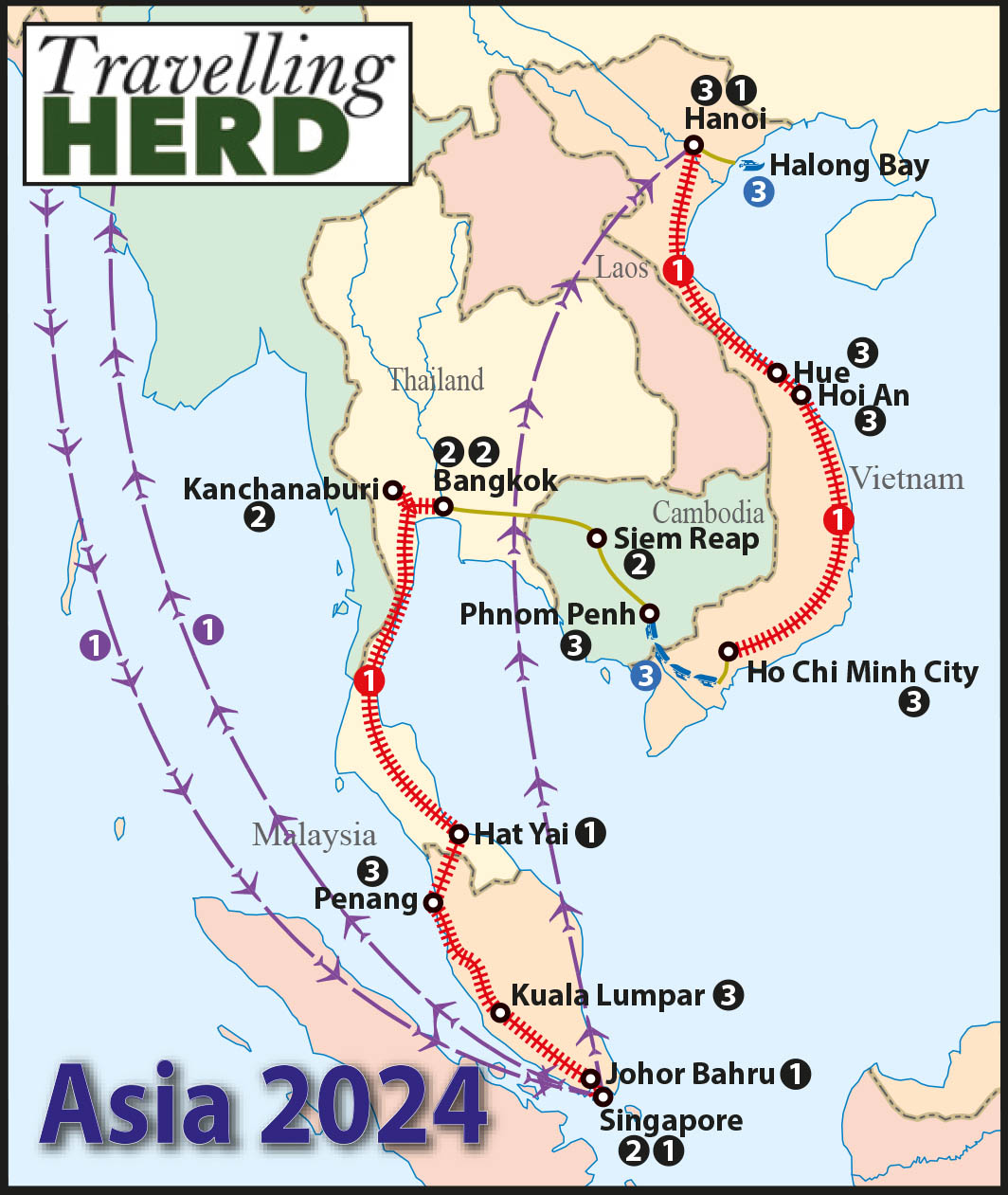

Route Map:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.