Read this blog: The one where we get more than we bargained for

Tuesday 19th March 2024

At the start of the day we paid 120,000 dong [VND] each and bought two tickets to Hội An old city with tear off strips which would allow us entry to five sites of our choice from about twenty listed on the leaflet we were given. This included museums, communal houses, assembly halls and old houses. We prioritised three places to visit, leaving two to be confirmed/chosen later.

The closest site to us was the Quan Âm Pagoda [Chùa Quan Âm] which is known for its large columns and is perhaps the oldest Buddhist temple in Hội An having been built in 1653 by residents of the Minh Huong villages. Although the ticket had perforations, a woman sat at the entrance armed with scissors to cut off one of the five entry slips.

The central courtyard was an oasis of peace and quiet.

From here we walked to our second site: the Phúc Kiến Assembly Hall, [Hội quán Phước Kiến] also referred to as the Fujian Assembly Hall and the Fukian Assembly Hall. Again, the attendant took a pair of scissors to our ticket. It was originally built in 1690 as a place for the Fujian-born community in Hội An to meet and socialise.

The gateway is very ornate with a decorative tiled roof [see Selfie of the Day] featuring dragons and other mythical creatures including Vietnamese unicorns. Inside is a courtyard with bonsai, vibrant floral planting schemes and small fountains.

A large fish in one of the fountains seemed to like having its head scratched by visitors, raising itself up out of the water to make the contact but Matilda was particularly taken with the porcelain animals, wearing their smart festive red bows.

The site was subsequently converted into a temple dedicated to Thien Hau, the goddess of the sea who keeps sailors safe. Inside vast spiral incense sticks were suspended, each with a label giving details of the person who had paid for it and the benefits they were hoping would be granted to their chosen recipients. If the length of time the spirals take to burn is an indicator, much good luck and prosperity is being generated here.

From here we walked down Trần Phú Street, one of the two main streets for people visiting Hội An to stroll along. The buildings are mostly one or two storeys tall.

The traditional architecture, the colourful clothes and hanging lanterns together with the absence of motorised vehicles make this a very pleasant place to promenade.

The famous Chùa Cầu or Japanese Bridge is at one end of the street and there is certainly a Japanese feel to this area. The bridge is unfortunately closed for refurbishment and the entrance is covered in a tarpaulin, printed to look as though it were still possible to walk through the bridge and across the small inlet. Matilda was very disappointed to find it closed.

The bridge was originally built in 1593 to link the prosperous Japanese trading community here with the Chinese quarter but, following an edict by the Tokugawa Shogun Iemitsu in 1663, strict regulations were placed on commerce and foreign relations and the Japanese trading community went into decline.

However, when we passed round beyond the tarpaulin, we found we could walk up on a scaffolding platform to look down at the work in progress without using up one of our five carefully managed entry tickets.

Refurbishment was an understatement: the whole covered bridge has been almost completely dismantled for repair.

From the Japanese Bridge we walked on to our third historic site – the Quan Cong Temple [Quan Thanh Mieu] built for the Cantonese community in the city.

We decided number four would be the Tan Ky Old House, a traditional merchant’s house built in 1741. It is still a family home and we were welcomed by a woman who introduced herself as “seventh generation”. She made sure she snipped off our entry strip and was carefully counting them as we entered the house.

Goods ready for sale were kept on the ground floor; those to be sold later were moved upstairs by means of pulleys. In 1961, the old house of Tan Ky was badly damaged by flooding but the original features were saved and it is not obvious to the untrained eye that there has been any water damage.

The name Tan Ky means Progress Shop and was first introduced by the second generation. The seventh generation has taken the name to heart and although Hội An is no longer a bustling port, stalls had been set up and through at the back of the house someone was cooking. We assumed this was the latest entrepreneurial money-making venture for the current generation of owners.

Further along the same street stands Quân Thắng Old House which is named after the successful Chinese merchant who built it in the late 18th century according to the principles of feng shui. The interior is decorated with intricate teak wood carvings. No one was waiting to tear or cut off our entry strip so we counted this as an extra visit for free.

Hội An was a prosperous port during the 18th and 19th centuries, and the owners of these old merchant houses were traders, sending boats up the river to bring goods back to sell to local and foreign merchants, particularly those from South-East Asia and Europe.

Unfortunately, the Thu Bon river was prone to regular flooding and gradually silted up making it impossible for large trading ships to use the port. By the beginning of the 20th century, very few international ships came to Hội An and both the town and its inhabitants became less prosperous. However these old houses provide a glimpse into Hội An in its trading heyday.

It seems every Vietnamese town has a market.

As with many other markets we have visited, the Central Market was selling everything from vital and necessary supplies for the local people to entirely unnecessary souvenirs for tourists.

With a ticket to spare we went in search of the “Trieu Châu Assembly Hall”, also known as the “Chaozhou Assembly Hall” which was built in 1845 by a community of immigrants from the Chaozhou region of China’s southern Guangdong Province. Unfortunately, when we arrived, it was closed so we still had a final entry ticket to use.

As the heat and humidity were becoming oppressive, we returned to our hotel and then strolled across the road to the Almanity Hoi A Resort and Spa for a cold drink in the shade by the pond. The peace was only broken when a young boy on the table next to us threw up. Perhaps it was the heat. Thankfully, staff and his parents (who had caught it in their hands) cleared up swiftly and efficiently.

Having rested through the heat of the day, we walked back to the old city, with one token still to use. A replica Shuinshen or Red Seal Ship stands at one end of Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai Street. Between 1604 and 1634, during the Tokugawa Shogunate, 86 such ships came to Hội An to trade.

Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai Street is the other main street for a promenade and is bedecked with colourful lanterns [see also the feature photo] and enterprising shops offer classes in lantern making.

We planned to use our fifth ticket at Cẩm Phô Community Hall which was built in the shape of Chinese character meaning ‘country’ and celebrates the local gods and ancestors of the Cẩm Phô village. It was restored in 1817. Once again, there was no-one to cut off a ticket, so we counted another free entry.

For our fifth and final entry ticket we went for the Old House of Phùng Hưng, Hoi An. This was built in 1780 and has been in the same family for eight generations. It is a two storey building and has a gallery overlooking the street.

The building stands on eighty columns and the architecture combines both Chinese and Japanese elements.

There are good views from the balcony.

Matilda’s stomach had been feeling a little unsettled and so later we opted to share for a relatively plain pizza, although it did have peanuts as an interesting additional topping [see Dish of the day].

Selfie of the day:

Dish of the day:

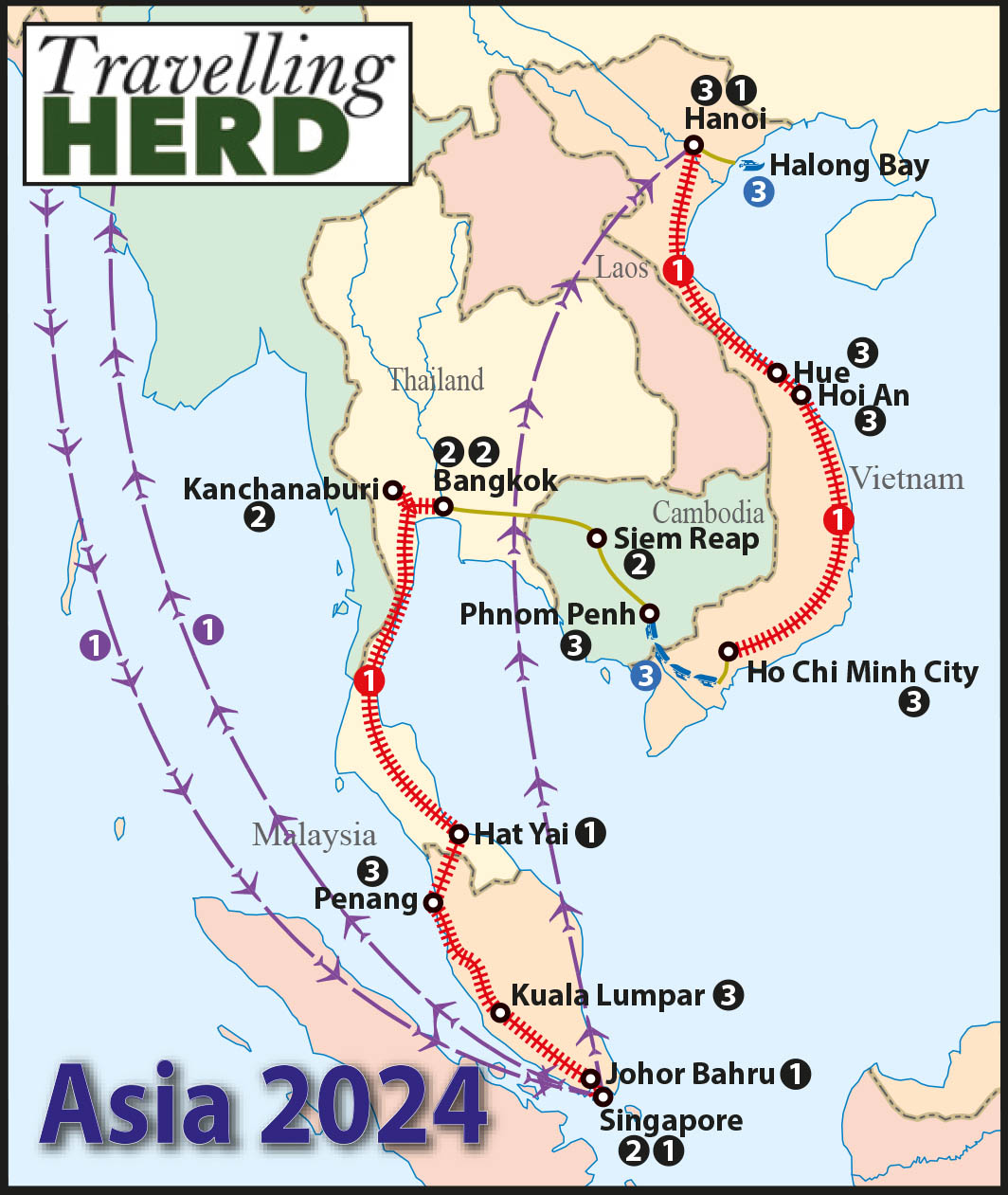

Route Map:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.