Read this blog: The one where Matilda struggles with acronyms

Saturday 16th March 2024

In a change from our usual pattern, Robert significantly overspent today’s culture budget by booking a 350km round trip to the DMZ & Vịnh Mốc Tunnels at a cost of 1,050,000 Vietnamese đồng [VND] each. That converts to approximately £82.

It turned out to be a very full day and as it went on Matilda in particular found it difficult to keep all the different military acronyms and allegiances straight in her mind so here is a key and some definitions for reference:

- ARVN – Army of the Republic of Vietnam [South Vietnamese forces]

- DMZ – Demilitarised Zone [area around the border between North and South Vietnam]

- PAVN – People’s Army of Vietnam [North Vietnamese forces: communist]

- National Liberation Front of South Vietnam – members of the communist movement in South Vietnam

- RVNAF – Republic of Vietnam Air Force [South Vietnamese forces]

- VC – Viet Cong – a general term for the communist movement in South Vietnam which developed from National Liberation Front of South Vietnam and also worked across Laos and Cambodia and used guerrilla tactics against the US

After the 1954 Geneva Accords, Vietnam was divided into North Vietnam and South Vietnam close to the 17th parallel. The DMZ was a narrow band of land, stretching for approximately 5km on either side of Ben Hai River, all across the country from Laos to the coast.

We were picked up from our hotel at 08:00 and a small select group of five set off with a guide and a driver. First we travelled north and along a 9km stretch of road which was the scene of extensive casualties during the American War and which became known as the Horror Highway.

During the Easter Offensive, between 29 April and 2 May 1972, the PAVN launched an extensive shelling campaign on Quảng Trị in order to gain control of the city. Consequently, almost all the 20,000 residents attempted to escape via the only available route – along Highway 1, which soon became virtually impassable.

Although three quarters of the people in the bumper to bumper convoy were civilians, 95 percent of the vehicles to the ARVN. A convoy comprising 2.5 ton trucks, flatbeds, tankers, small trucks, jeeps and 15 ambulances constituted an obvious target for the PAVN which shelled the column mercilessly, causing untold casualties.

Our first stop was Quảng Trị Ancient Citadel. This was a nineteenth century fort, similar to the one in Huế, which was used by both the French colonial regime and the American-backed southern regime, after the end of WWII.

It is also the site of the Second Battle of Quảng Trị, fought between the combined forces of the PAVN and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam against the US Armed Forces and the ARVN.

During the bombardment it is said that up to 20,000 artillery shells per day were fired at an area of less than 3 square km. After 81 days of heavy bombardment, on September 19, 1972 the US and the ARVN recaptured the citadel which had, by then, been almost completely flattened. Only part of the archway of the east gate and some sections of walls remained standing.

Some restoration has now been undertaken and the site has been turned into a sculpture park and place of memorial honouring the dead.

Three of the gateways into the citadel have now been replaced and the gateway which partially survived has been restored and rebuilt but retains the original metal gates damaged by bullets and shrapnel.

The central memorial mound contains the remains of many solders who could not be identified and 81 steps lead to the platform on top representing the 81 days and nights of fierce fighting. Unfortunately we were both wearing shorts and exposing our knees so were not allowed to climb up this monument.

The sculptures are both modern and dramatic and we felt we could have spent longer here but there was a busy itinerary for the day.

The next stop was Sân bay Biên Hòa, the Sân Bay Air Base, which was used by the RVNAF. Between 1961 and 1973 units from the US Army, Air Force, Navy and Marines were stationed here. The wreckage of military equipment stands by the entrance but there were a number of incidents on the base, including ground accidents and explosions so this need not have been the result of enemy attack.

Elsewhere on the site stand a range of abandoned US aircraft and vehicles which were in common use during the Resistance war against America.

In early April 1975 PAVN forces were approaching the ARVN’s last defensive line before Saigon.

On the morning of 15 April a PAVN squad of elite combat engineers [sappers] penetrated security, entered the base and blew up an ammunition dump. The PAVN then began shelling the base, blasting craters in the runways which severely restricted landing and take off.

It is difficult to imagine the base in war time as when we visited a quiet calm had descended with the clouds apparently touching the mountains.

In June 1962 two ARVN soldiers guarding the base perimeter were surprised and killed by the VC. Although the VC were often poorly equipped, having cloth hats rather than metal helmets, they mounted a highly effective guerilla war against US troops. As a result the jungle north of the area was cleared in July using Agent Orange spread by helicopter to prevent VC soldiers using the dense foliage as cover.

The defoliant Agent Orange was stored at the site for decades and the Sân Bay Air Base has been described as the most contaminated site in Vietnam. In April 2019 a 10-year project was announced to decontaminate the base costing America US$183 million.

There are also the remains of defensive trenches here which are perhaps deeper and more robust but otherwise not very different from those we saw at Sanctuary Wood, Hill 62 [See our blog RWC #12: Ypres – Lest we forget].

The Hồ Chí Minh Trail [Đường mòn Hồ Chí Minh] was a network of roads, paths and trails running from North to South Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia which facilitated the transport of manpower and materials to support the PAVN and the VC forces.

Next we stopped at Cầu Đakrông or Dakrong Bridge which was a vital part of this network. During the American War the bridge was made of iron and was repeatedly destroyed by bombing to disrupt supplies and then rebuilt by local people.

After 1975, the Cuban government helped Vietnam replace Dakrong Bridge to improve the country’s transport links. Unfortunately this bridge was swept away in severe floods in 1999 and was then reconstructed in 2000 funded by both the Cuban and local governments. The remains of the original ‘Cuban’ foundations are still visible.

We got out of our minibus and walked across the bridge [see Selfie of the day] before being taken to Dong Ha for lunch [see Dish of the day] before driving on to the old border between North and South Vietnam which runs down the centre of the Bến Hải River.

On the south side stands a monument called Desire for National Reunification also referred to as the Unified Memorial of Hope Monument commemorating the 21 years when the country was divided.

The Hiền Lương Bridge over Bến Hải River was at the centre of the DMZ. It sits on the 17th parallel and a white line marks the centre of the river representing the border between North and South Vietnam.

The foot bridge is painted different colours either side of this line. Apparently if the South Vietnamese painted the bridge yellow, the North Vietnamese would swiftly repaint the bridge blue, as a visual way to claim ownership of the whole length of the bridge. Now the southern half remains yellow and the northern half is painted blue to commemorate this colour war. Propaganda would be broadcast loudly, by both side, across the river.

The bridge was destroyed by bombs several times but in 2001 it was restored to the original French design. A second bridge has been built to take vehicles [visible in the background].

The Frontier flag flies from the Hiền Lương flagpole on a huge decorated round pedestal which features detailed and elaborate mosaics in the style of Socialist modernism. The mosaic depicts scenes from life during the war including the negotiations and everyday activities such as planting rice.

Our final stop was the Vịnh Mốc Tunnel complex. Believing the villagers in this area to be supporting the North Vietnamese, the US bombed the area extensively and repeatedly to try evict the villagers.

They had nowhere to go but downwards. The first tunnels were dug in 1966 to a depth of 10m but the Americans designed bombs which could penetrate this deep. Above ground there are examples of the ordinance which was launched at the area and many bomb craters are still visible.

Faced with this more penetrating artillery, the villagers began to dig deeper, eventually reaching a depth of 30m.

The whole complex was excavated in several stages and was used until early 1972.

The complex grew to include wells, kitchens, rooms for each family and spaces for healthcare. The 14 villages/communes in the area each dug and kept their own tunnel. Around sixty families moved to the tunnels to escape the bombing; and 17 children were born inside the tunnels.

Without wishing to appear flippant, when we exited the tunnels by the coast after just a short visit underground, the ability to stand upright, breathe fresh air and hear the sound of the waves on the shore was a very welcome return to the outside world.

Between 1965 and 1968 soldiers and villagers dug a network of trenches connecting house to field; village to village and field and village to tunnels in the Vinh Linh district. People travelled not only on foot but also on bicycle and the trenches were used to teach lessons as well as to move cattle and pigs around the region. The trenches provided protection from smaller bombs and for those who could not reach the tunnels when an air raid started.

From here it was about a two hour drive back to Huế. Our guide was enthusiastic and told us factual details about the things and places we saw but we felt we would have liked more contextual information about the conflict and more time at some of the sites even if this meant missing one of the places off the tour.

Nevertheless it was an informative day and left us pondering the futility of war and regretting the avoidable loss of so many lives.

Selfie of the day:

Dish of the day:

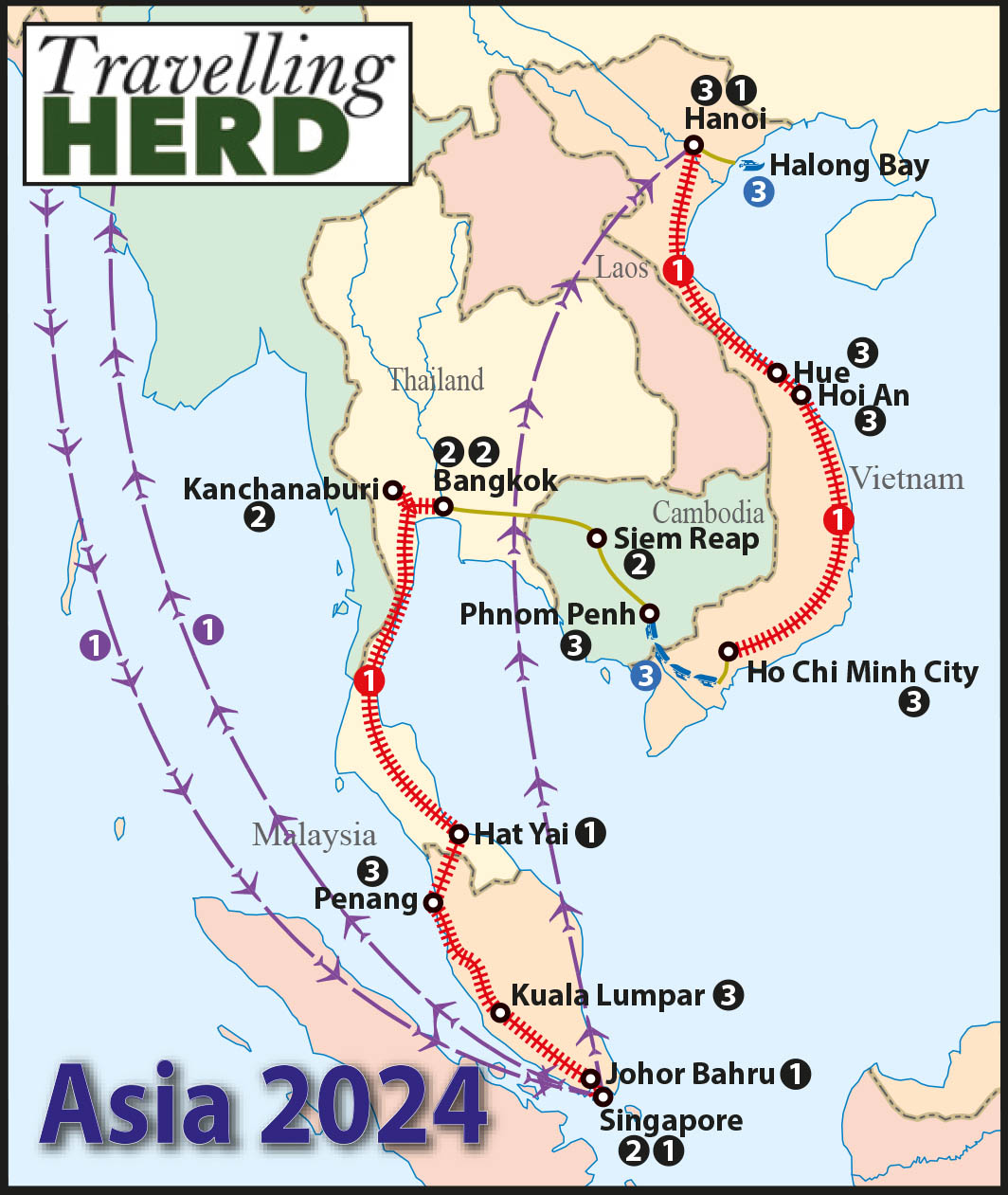

Route Map:

Discover more from TravellingHerd

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.